Cary Wu, York University, Canada

America’s gun violence affects not only just those killed, injured or present during gunfire, but research suggests it can also sabotage the social and psychological well-being of all Americans.

Gun violence is widespread in the United States. More than half a million Americans have been murdered by those brandishing firearms over the last four decades.

Many more are physically or psychologically injured by guns. A Pew Research Center survey reports that, overall, one in four Americans (23 per cent) say someone has used a gun to threaten or intimidate them or their families. This includes a third of Black Americans (32 per cent).

Over the course of their lifetimes, nearly all Americans of all racial and ethnic groups are likely to know a victim of gun violence in their social network.

But there’s not been much scholarly attention dedicated to the social and psychological impacts of gun violence on Americans and American society.

My recent research shows that such widespread gun violence, both fatal and non-fatal, has a detrimental effect on Americans’ trust in each other. That erosion of trust is often long-lasting and has a greater impact on Black Americans.

The high likelihood that all Americans were either threatened or shot with guns from the 1960s to the 1990s could also be a plausible explanation for the half-century decline in trust in public institutions in the U.S.

Generalized trust and why it matters

People’s trust in others they don’t personally know, or generalized trust, reflects their expectation of good will and benign intent from most people.

Trust matters. Those who trust other people are better off financially, stand at a higher socioeconomic status, are more satisfied with their life, generally happier, have better health and even tend to live longer.

Trust can also explain why some societies function better, are richer, safer, more cohesive and more democratic.

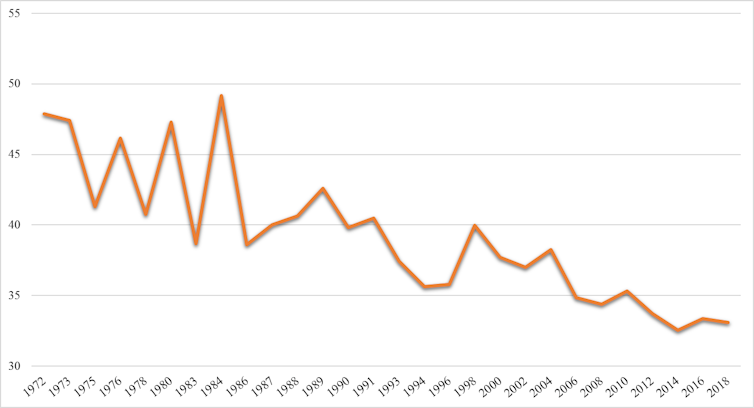

American society is currently facing a crisis of trust. While in neighbouring Canada, more than 58 per cent Canadians say most people can be trusted, only about 33 per cent of Americans report they have trust in their fellow citizens.

The proportion fell by almost half from 1960, when 59 per cent of American citizens said that most people can be trusted.

Where does trust come from? Some scholars believe that people are trusting because that’s how they’re raised. Others suggest that trust is dependent on contemporary social experiences and contexts.

Gun victimization and trust

Research into how gun victimization affects trust provides a way to test this long-standing debate.

To do so, we need micro-level data from individuals on their own personal experiences of gun violence, but it can rarely be found. This is partly due to what’s known as the Dickey Amendment in the U.S., which was enacted in 1996 to ban federal funding for gun violence research.

The only data I can find is from the U.S. General Social Survey. The survey included questions over 15 years, in its 1973-1994 surveys, asking a nationally representative sample of Americans whether they had experienced gun victimization. Questions included: “Have you ever been threatened with a gun, or shot at?” If so, the surveys asked, when did it happen — when respondents were children or adults?

Unfortunately, these questions were discontinued in 1996 and onwards, likely due to the Dickey Amendment.

While the data is relatively old, research findings could be very relevant today. This is especially true in recent years since gun crime is on the rise.

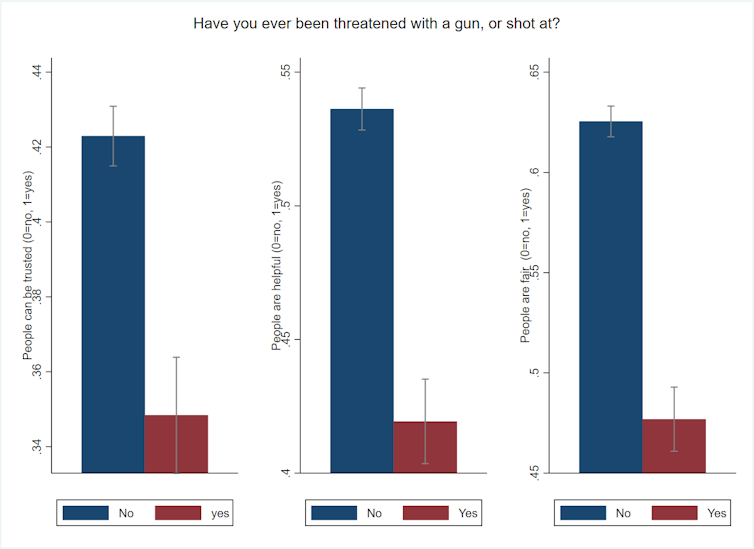

My analysis of the data from the General Social Surveys shows that those who had experienced being threatened by a gun or suffering a gunshot wound were significantly less likely to say that most people can be trusted, to say that people are helpful and to say that people are fair:

Gun victimization could have occurred in childhood, in adulthood or repeatedly during both childhood and adulthood. It could affect trust differently when it occurred at different time periods in life. In terms of the size of the impact, for example, repeated gun victimization had the strongest effect, followed by adulthood victimization and then childhood victimization. See below:

Individuals who later achieve higher socioeconomic status are better able to recover from the psychological impact of childhood gun victimization.

This finding suggests that trust evolves according to new life experiences.

The Black-white gap in trust

Compared to whites, Black Americans are less likely to say they can trust in others.

Blacks are also much more likely to experience gun victimization. The General Social Survey data shows that Black Americans have about 60 per cent higher odds of experiencing gun victimization than white Americans.

Long-standing systemic racism has also made Black Americans less likely to get ahead in terms of socioeconomic achievements. Considered all together, this could help explain why the trust gap between Black and white Americans has barely changed for decades.

Vicious circle

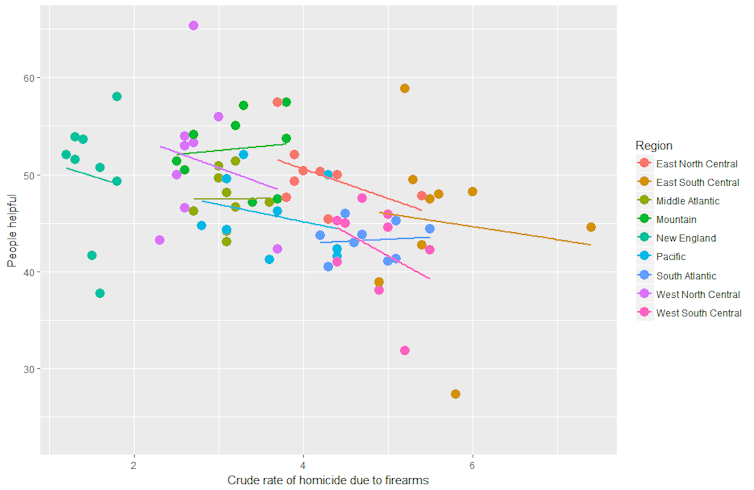

The preponderance of personal gun victimization is often a neighbourhood disadvantage. When communities have higher percentages of people who were victimized by guns, their withdrawal from community life, their higher sense of powerlessness and their eroded trust in their fellow citizens can affect everyone living in these neighbourhoods and cities.

Harvard professor Robert Putnam has long pointed out that places with low trust may become trapped in a “vicious circle in which low levels of trust and cohesion lead to higher levels of crime, which lead to even lower levels of trust and cohesion.”

My analysis shows that places with higher percentages of people who were victimized by guns results in them feeling less trustful, and over time trust erodes even further because they’re living in neighbourhoods with higher levels of gun violence.

But to fully understand how gun violence affects Americans’ everyday life, more data needs to be collected and more research needs to be conducted, especially as the country continues to grapple with the ever-increasing scourge of violence involving firearms.![]()

Cary Wu, Assistant Professor, Department of Sociology, York University, Canada

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.