Thomas Klassen, York University, Canada

After a surreal election campaign in the midst of a pandemic, we’re still not sure of the outcome — either Donald Trump won a second term, or Joe Biden will become the next president. Although pre-election polls showed Trump heading for certain defeat, he once again defied pollsters.

Viewed by many as a referendum on Trump’s first term, and indeed on the man himself, the election was one of the most tumultuous in American history. The outcome is still not clear because ballots are still being counted in key battleground states.

Like Hillary Clinton four years ago, Joe Biden positioned himself as the keeper of former president Barack Obama’s progressive ideology. In contrast, Trump promised an “America First” platform of limiting immigration and protecting United States trade interests — a stance that has included, at times, taking aim at Canada, the country’s closest trading partner.

Read more: Canada needs to see the U.S. and its trade motives clearly

What’s ahead for Canada?

For Canadians, a Trump victory would essentially mean more of the same but perhaps at a lower decibel level.

Justin Trudeau has managed his relationship with Trump as well as anyone could. Pipelines, steel, aluminum, agriculture and forestry products will continue to be on Trump’s agenda and will be trade irritants between the two countries.

The reality is that Canadian interests — whether on trade, global climate change, foreign affairs or other matters — don’t align with America’s, regardless of the president in power.

A President Biden, on the other hand, will mean a period of uncertainty as a new administration takes charge. But if Trump remains in power, there will be little ambiguity in the Canada-U.S. relationship.

Canada and the battleground states

As in 2016, this election will be decided by a trio of battleground states — Pennsylvania, Michigan, Wisconsin. The ballots are still being counted, but Biden has been declared the winner in Wisconsin, though Trump is demanding a recount. Trump won all three states in 2016, which helped carry him to victory.

These swing states are critical because they routinely shift between voting for the Democratic presidential nominee and the Republican nominee. Most states vote for the same party election after election. California, for example, with its 55 electoral college votes (more than one-fifth all the electoral votes needed to become president), has overwhelmingly voted Democrat for decades. With little likelihood of that changing, both Biden and Trump did almost no campaigning in California.

In contrast, Ohio — one of the battleground states won handily by Trump this election — sways back and forth between Democrats and Republicans. And since 1944, the state has only once voted for the losing candidate, choosing Richard Nixon over John F. Kennedy in 1960.

These battleground states — some of them lining the Canadian border — played an outsized role in this campaign. Trump and Biden did most of their campaigning in these states during the past months knowing that every vote they could obtain counted.

Trump’s “America First” policies resonate with voters along the northern border, some living so close to Canada that they may imagine the loss of their assembly plant or farm to a foreign entity, as outlandish and unlikely as that may seem to Canadians.

Perhaps one day Trudeau will have the opportunity to remind Trump, if he wins re-election, that his second term was in large measure due to support from the states with the closest economic and cultural ties to Canada.

Trump’s imprint on the U.S.

Beyond his populist style, Trump will have four more years to leave deep marks on America should he win a second term. He is the only person ever elected president without prior government or military experience. He is the oldest person to serve as president.

During his tenure, three Supreme Court justices were confirmed, reshaping the court for a generation. Barack Obama, George W. Bush and Bill Clinton only had two justices confirmed during their eight-year terms. Likely more appointments could occur during a second term.

The question for Trump is whether to seek out new avenues to leave a legacy, or to solidify the shifts he has engineered so far. If the former, then working more closely with Canada on matters such as trade disputes with China or immigration policy would be reasonable options. This could certainly happen under a Biden presidency — Obama and Trudeau had a “bromance,” and Biden could pick up where Obama left off in terms of a positive working relationship with his Canadian counterpart.

Regardless, if he’s won re-election, Trump — perhaps for the first time in his life — may feel he has nothing more to prove. This may create openings for policy innovation. Canadian policy-makers would be wise to seek to present some of these to the White House, such as on tourism and regional development that are win-win for Canada and the U.S.

Biden and the Democrats

In some ways, Biden was an odd choice as standard bearer for Democrats eager to portray themselves as a party of new ideas and change. The last five Democratic presidents — Kennedy, Lyndon Johnson, Jimmy Carter, Bill Clinton and Obama — were, on average, 30 years younger when they took office than Biden.

Many in Canada prefer Biden to Trump. Democratic presidents have historically had better personal relationships with Liberal prime ministers than Republican presidents have. A Biden presidency holds the promise that Canada could be treated with more respect and care, even if the underlying disagreements remain.

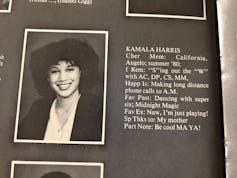

Kamala Harris is also a bright spot for the U.S.-Canada relationship.

Regardless of whether Biden or Trump is the winner, she’ll have an excellent opportunity to become the Democratic presidential nominee in four years (should a President Biden opt not to run again). Having spent her teenage years in Montréal, Canadians dismayed at the prospect of four more years of Trump can seek solace that the next president may be someone with a personal Canadian connection.![]()

Thomas Klassen, Professor, School of Public Policy and Administration, York University, Canada

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.