Sarah-Patricia Breen, University of Saskatchewan

The realities of rural Canada are poorly understood, with the word rural often used as though it’s a monolithic thing.

In February, a news article published across Canada identified a rural-urban split in the distribution of the Canada Emergency Response Benefit, known as CERB. The article identified a higher proportion of urban residents relying on CERB. The article provided perspectives from various people offering explanations about the possible reasons for the difference.

These explanations featured generalizations about urban reliance on tourism resulting in greater need, and rural reliance on natural resources that “wouldn’t have been hit as hard” by COVID-19.

This narrative no doubt came as a surprise to tourism-dependent rural communities, where COVID-19 has had significant impacts on employment and exacerbated tensions between residents and urban visitors.

Read more: Do you have a right to go to the cottage during the coronavirus pandemic?

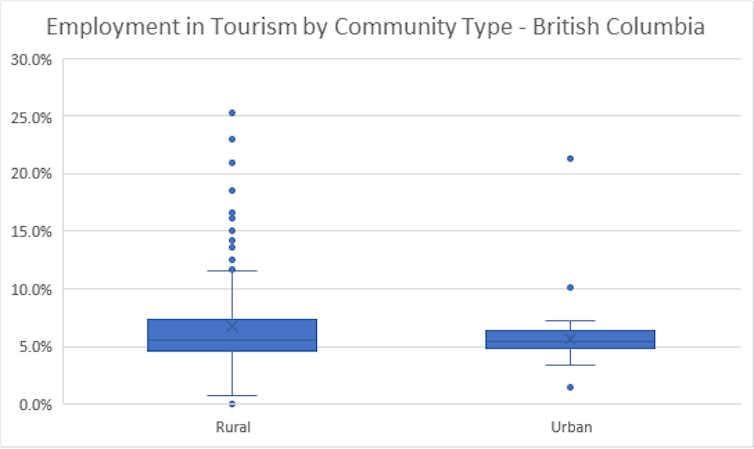

The tourism sector, in fact, is critically important to rural communities. In British Columbia, for example, rural communities are on average more dependent than urban centres on tourism as a source of employment, and communities with the largest dependence on tourism are rural.

The notion that communities reliant on natural resource sectors were not as hard hit by COVID-19 also likely came as a surprise. These communities continue to experience layoffs and costly changes to business practices.

Statistics Canada data shows that employment in forestry, fishing, mining, oil and gas is below previous years’ levels.

The use of social programs is complex

Just as there are unique dynamics influencing different sectors, the use of support programs by rural Canadians — whether they’re federal or provincial support programs, aimed at businesses or those who have lost work — is also complex. Use is not only influenced by need, but by other factors, like the ability to access support.

Treating rural communities as a monolithic entity conceals the range of experiences across rural communities. The resulting narrative can create false impressions — including the notion that rural communities are doing well in comparison to urban areas during the COVID-19 pandemic.

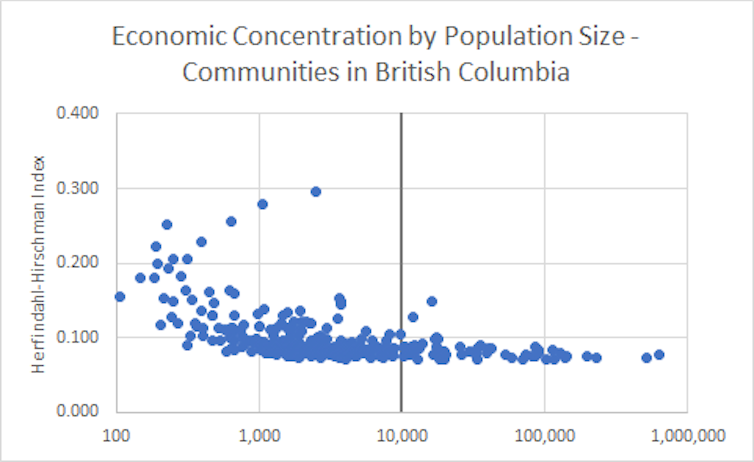

If we consider economic concentration in British Columbia by community size, we see that rural communities on average are less economically diverse. However, we also see high levels of variation among rural communities — some are as diversified as urban centres.

Data from other provinces and territories will tell a different story — because there is far more than a single rural story.

Rural data matters

All of this illustrates a larger pattern of failing to recognize rural diversity. This pattern contributes to policy failures that impact rural realities and limit future opportunities. The sheer number of communities in rural Canada, along with a lack of organized and accessible community-level data, often leads governments to develop policies that do not account for the differences between rural and urban, let alone differences across rural regions.

Governments tend to understand urban and rural as two contrasting groups, and that rural communities need help catching up with urban centres. This is wrong on two levels.

First, it does not consider variations within each group. Second, it assumes that development for rural communities means becoming more urbanized. As a result, one-size-fits-all policies are created that don’t account for the realities of rural communities.

Policies are time and again built on this binary understanding, mostly because this simplification makes policies easier to create and implement.

A first step to developing better policies is to improve policy-makers’ knowledge of rural communities by compiling and organizing community-level data in a user-friendly way. Although it can be difficult to obtain data, especially for small and Indigenous communities, much of what is available is under-used. Improving access would help to close this gap.

However, data access is not enough to bring about better policies. Decision-makers need to be convinced of the need to recognize rural diversity.

How composite indicators can help

That is where composite indicators (CI) can play a role. CIs — like the United Nations’ Human Development Index — can synthesize multidimensional concepts into a single score through the compilation of individual indicators.

The ability to simplify complex issues makes CIs powerful tools to draw attention to a topic. A well-designed CI can shed light on a range of different rural realities and spur a conversation about the need to acknowledge rural diversity in policy.

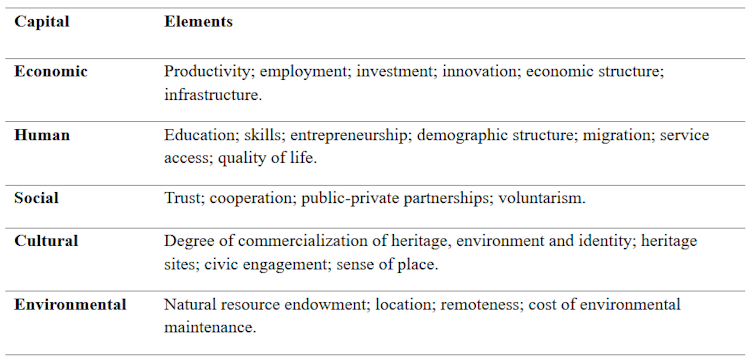

One approach to building a rural CI is to base it on five types of capital. How communities perform in each of these areas can help policy-makers understand their needs and barriers.

CIs are one tool to shine a spotlight on rural diversity and provide insights into rural realities. However, moving away from policies that treat rural communities as an undifferentiated group will require more than a single tool.

It requires acknowledgement that viewing rural Canada as monolothic and the policies — and news stories — built on that assessment have limited value for rural communities. As Canada prepares for post-pandemic life, rural communities would benefit from flexible policies that support them in achieving their goals.

Diogo Oliveira, who graduated with a master’s in public administration from the University of Victoria, co-authored this piece.

Sarah-Patricia Breen, Adjunct Professor, Public Policy, University of Saskatchewan

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.