The COVID pandemic triggered an unprecedented rise in deaths around the world, leading to falls in life expectancy. In research last year, we found that 2020 saw significant life expectancy losses, including more than two years in the US and one year in England and Wales.

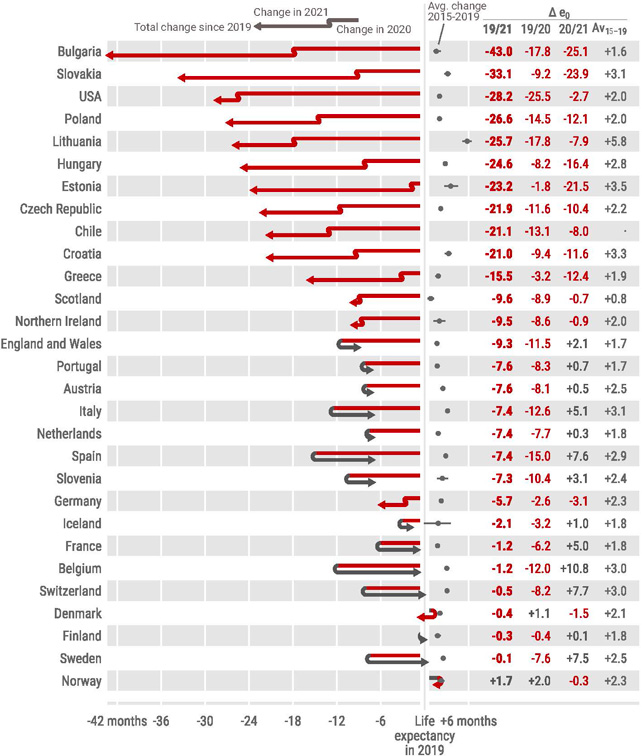

In a new study published in Nature Human Behavior, we have now shown that, in 2021, life expectancy rebounded somewhat in most western European countries while eastern Europe and the US witnessed additional losses. However, only Norway beat its pre-pandemic life expectancy in 2021, and everywhere is worse off than it would likely have been without the pandemic.

We knew the outlook for 2021 was mixed, with the excitement of vaccine rollouts tempered by huge numbers of infections caused by a series of new and highly transmissible variants.

To assess the impact of these changes on life expectancy, our research team at the University of Oxford's Leverhulme Centre for Demographic Science and the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research gathered data from 29 mostly European countries (plus Chile and the US).

Life expectancy is a measure we use to summarise the mortality pattern of a country in a given year. It's calculated based on deaths from all causes, so it doesn't depend on the accuracy of recording COVID deaths, and can give us a broader picture of how the pandemic affected mortality.

Life expectancy is not a prediction of the lifespan of a baby born today. Rather, it's the number of years someone born today could expect to live, if they lived their whole life with the mortality rates of the current year (or 2021 in the case of our research).

So it's a snapshot of current mortality conditions, if they were to continue without any improvements or deterioration.

Demographers find life expectancy a very useful summary measure of population mortality because it's comparable across countries and over time.

Large swings upwards or downwards can tell us something dramatic has changed, as it has with COVID. The size of these drops allows us to compare mortality shocks across time and place.

Life expectancy during COVID-19

We found there was much more variation between countries in the impact of the pandemic on mortality in 2021 compared with 2020.

Life expectancy went down for virtually every country we studied in 2020, with the exception of Denmark and Norway. But in 2021, for some countries, life expectancy improved from 2020, while for others, it got even worse.

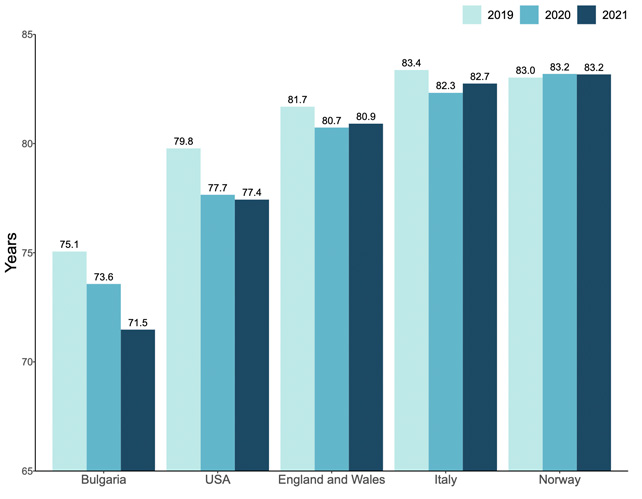

The further falls we found in eastern Europe were likely because the region avoided some of the early COVID waves during 2020, combined with lower vaccine uptake when large waves did arrive in 2021. Bulgaria was the most extreme example, with a staggering loss of 3.5 years since 2019 (1.5 years in 2020 and two years in 2021).

Despite an early vaccine rollout, the US continued to diverge from western Europe with an additional loss of almost three months in 2021 after losing over two years in 2020. The US had lower vaccine and booster uptake compared with western European peers, likely accounting for some of this difference in 2021.

But life expectancy in the US has been lagging behind European countries for many years, so some of this US disadvantage may reflect underlying health vulnerabilities that were exacerbated by the COVID pandemic.

While most of their life expectancy losses can be attributed to confirmed COVID deaths, the US also saw continued increases in deaths due to drug overdoses.

England and Wales fell somewhere in the middle, gaining 2.1 months in 2021 after a loss of almost a year in 2020.

Even for countries that did relatively well, COVID still derailed the trajectory of mortality improvements we would normally see year on year.

Life expectancy at birth by country, 2019–2021

Overall, deaths shifted slightly towards younger people in 2021 compared with 2020.

This is likely due to better vaccine coverage and more precautions at older ages.

Indeed, countries with better vaccine coverage for those over age 60 did better in life expectancy.

Mortality over age 80 in the US even returned to pre-pandemic levels. But overall life expectancy was worse in 2021 due to worsening mortality under age 60.

We also compared recent life expectancy declines with historical crises which have led to significant deaths.

Losses to the degree we've seen during the pandemic haven't been recorded since the second world war in western Europe, or since the breakup of the Soviet Union in eastern Europe.

Meanwhile, previous flu epidemics have seen fairly rapid bounce-backs of life expectancy levels. COVID's impact so far has been larger and more persistent, belying the common claim that it's "just like the flu."

Limitations, and looking ahead

Because life expectancy estimates require fine-grained data on deaths by age and sex, we were not able to calculate life expectancy accurately for all countries around the world in this study.

We know that countries such as Brazil and Mexico suffered large life expectancy losses in 2020, and it's likely that they continued to suffer additional losses in 2021.

COVID mortality in countries like India may never be accurately tallied due to data limitations, but we know the death toll has been substantial.

Looking forward, the prospects for life expectancy recovery in 2022 and beyond are still hazy. We expect continued divergence due to country differences in vaccine and booster uptake, previous infections, and continued public health measures (or lack thereof).

The full impact of delayed healthcare and ongoing health system strain remains to be seen.

New variants that evade existing immunity are likely to arise, and the longer-term impact of COVID infections on the health of survivors is a big unknown.

While we hope that mortality will return to pre-pandemic levels (and even start improving again), sustained excess deaths in England and elsewhere in 2022 suggests we have not fully bounced back from the mortality impact of the pandemic, and the path to recovery remains uncertain.![]()

Jennifer Beam Dowd, Professor of Demography and Population Health, University of Oxford and Deputy Director, Leverhulme Centre for Demographic Science, University of Oxford; José Manuel Aburto, Brass Blacker Associate Professor of Demography at LSHTM and Marie Sklodowska-Curie Fellow at Leverhulme Centre for Demographic Science, University of Oxford, and Ridhi Kashyap, Professor of Demography & Computational Social Science, University of Oxford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.