Martin Andresen, Simon Fraser University

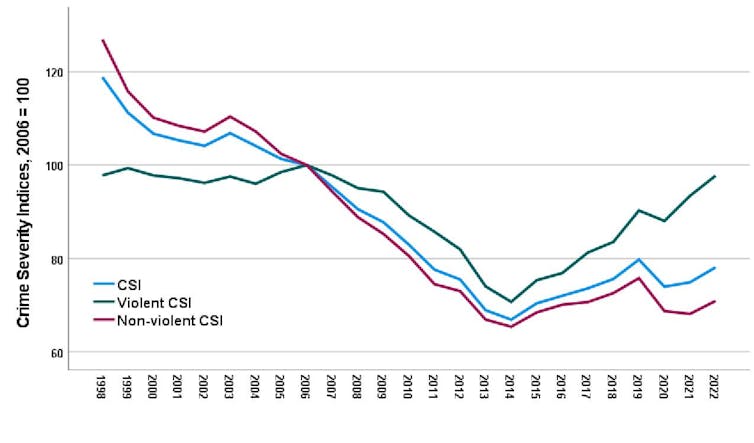

Every summer, Statistics Canada releases crime rate and crime severity data for the previous year. This year, Canada’s Crime Severity Index (CSI) increased by 4.3 per cent, the violent CSI increased by 4.6 per cent, and the non-violent CSI increased by 4.1 per cent. Moreover, aside from a drop during the COVID-19 pandemic, these indices have been on the rise since 2014.

An April 2023 poll found that 65 per cent of Canadians felt crime has gotten worse compared to before the pandemic. Conservative Party leader Pierre Poilievre has criticized the Liberal government for the rising crime figures in recent months.

Canada’s new justice minister, Arif Virani, said it was empirically unlikely that Canadians are less safe, but that the government would act to address feelings of growing insecurity.

But what is the CSI and what do changes in crime stats mean for Canadians?

What is the Crime Severity Index?

The CSI was introduced in 2009 and represented the first major change in measuring crime in Canada since the 1960s. Its purpose was to identify changes in the seriousness or severity of crime reported to the police.

The CSI is calculated like a crime rate, but different crimes are given a different weight, or importance, based on their severity. Without this kind of system, a community that has 10 low-level assaults will have the same violent crime rate as another that has 10 homicides because each incident would be given the same weight.

The CSI accounts for this by using different weights for different crime types: approximately 80 for assault level 1, 7,000 for homicide and one for gambling. These weights are based on sentencing decisions in the court system.

Understanding the data

At first glance, the CSI is great because it allows us to determine which areas experience more violence. However, there are at least three issues when considering what changes in the CSI mean for most Canadians.

First, the CSI must be considered over longer periods of time than year-to-year fluctuations. We now have the CSI for 1998-2022, 25 years of data. Yes, the CSI has been increasing since 2014, but it is still much lower than it was 25 years ago.

Crime has been falling around the world, including Canada, since about 1990. It may be the case that 2014, for Canada, was just the low point for crime. Because of this, relatively small changes in incidents will have large percentage changes.

Second, because the CSI is calculated in a similar fashion to crime rates, places with lower populations will be “punished” by the CSI. For example, in a city of one million people, one homicide will lead to a homicide rate of 0.1 per 100,000 people. However, in a city of 15,000 people, one homicide will lead to a rate of 6.67 per 100,000 people.

Now if you add in the weights used in the CSI, this disparity becomes magnified. To be clear, the math is not wrong — it is just that the statistic has its limitations. The CSI is fine for Canada, its provinces and larger metropolitan centres. But, for the rest of the country, the CSI should be interpreted with caution.

Third, crime is usually concentrated in specific areas. Across the world, including Canada, one-half of crime reported to the police occurs in approximately five per cent of the city. These places are, generally speaking, areas that experience more poverty, mental health and addiction problems, and other social challenges.

In short, those who are already suffering most, especially post-pandemic, are being victimized more with these increases in crime in Canada; this has been shown in Vancouver and Saskatoon.

Reducing crime

What should our takeaway be here? We need to be careful of how we interpret the CSI. Crime has been increasing the past eight years: homicide, sexual assault, assault (particularly with a weapon) and vehicle theft are all increasing more than average. So, despite my caveats, crime has been increasing of late, particularly violent crimes.

The notable common thread in all of the media coverage of these violent attacks is the presence of mental health issues, addiction, homelessness and poverty. How did we get here? Over the past 40 years, conservative governments have defunded social programs and social services.

A result of these changes has been a decrease in social welfare and increases in social ills. Where we are today is the result of a 40-year process that we cannot expect to reverse in short order. We need to reinvest in social programs and services, knowing it will take time to see an impact.

Putting government funding back into social services is a large component of the Defund the Police movement. Rather than continuing to spend on reactive models such as policing that do little more than criminalize poverty and disadvantage, we need to reinvest in preventive strategies that actually work.

To prevent crime, governments need to invest more in existing social welfare programs and reestablish social services such as basic income.

This spending on social welfare services and basic income should be viewed positively across the political spectrum as well. The provision of basic income and social services would both support vulnerable populations and be cost-effective.

If we are concerned about crime and its severity, we should support reinvesting public funds into preventative strategies such as housing, mental health care, basic income and addiction services.![]()

Martin Andresen, Professor of Criminology, Simon Fraser University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.