USA & CANADA (901)

Latest News

Canada needs to move beyond poorly enforced bribery laws and tackle corruption’s root causes

Thursday, 02 November 2023 04:50 Written by theconversationCanada’s enforcement of laws against foreign bribery is weak, according to a recent report from the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

A working group from the OECD has found that, in the nearly 25 years since Canada passed the Corruption of Foreign Public Officials Act and signed onto the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention, only two people have been convicted of foreign bribery and four companies have been sanctioned.

Corruption is a serious issue and a very costly threat to Canada’s foreign trade and international reputation. Although there are no reliable statistics on the exact amounts lost to global corruption, estimates range in the trillions of dollars. The OECD said Canada must do more to deter foreign bribery and other corruption offences.

Our recent research sheds light on both Canada’s slow rate of progress in combating corruption and the OECD’s failure to get to the root causes of corruption.

SNC-Lavalin controversy

In the past, Canada has had difficulty passing and enforcing laws against powerful multinational corporations. Nowhere is this more clear than in the SNC-Lavalin controversy.

In 2018, Parliament added remediation agreements to the Criminal Code of Canada in a budget bill. These agreements offer a new way to settle criminal charges for crimes like corruption. Unlike plea bargains, they provide a means to resolve cases without convictions. This mitigates the negative effects on those not involved in crime, like employees and pensioners, while still imposing consequences.

Remediation agreements attracted little attention until news broke that Kathleen Roussel, the head of the Public Prosecution Service of Canada, refused to invite engineering and construction giant SNC-Lavalin to negotiate such an agreement in 2018.

SNC-Lavalin had hoped to use a remediation agreement to settle criminal charges relating to a multi-year scheme of foreign bribery and corruption in obtaining government contracts in Libya. It made no secret of being unhappy with the decision of prosecutors, which it tried unsuccessfully to challenge in court.

A few months later, another political scandal erupted when the media reported Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and his staff had pressured then-attorney general Jody Wilson-Raybould to overrule Roussel’s decision, leading to Wilson-Raybould’s resignation. It was later determined the prime minister’s actions violated the Conflict of Interest Act.

The state of affairs

In 2022, we conducted a survey asking how lawyers, consultants, government officials and academics felt about the state of anti-corruption laws in Canada. We asked their opinions on what corruption is, what acts are most serious, what countries are most corrupt and what remedies they would recommend.

The majority of participants accepted the standard legal definition of corruption, which involves bribery offered by a private agent to a public official.

While acknowledging the existence of corruption in Canada, participants believed it was most severe and widespread in non-western or developing nations, and less prevalent among fellow middle-class professionals. While toxic corporate cultures were identified as contributing to corruption, weak individuals were seen as the primary issue rather than built-in incentives to maximize profit.

They all criticized the federal government’s enforcement record but saw the introduction of the Beneficial Ownership Registries in the 2023 budget as promising if enforced. This registry requires companies to reveal the true owners behind shell companies.

One corruption professional said:

“There is no central government agency that is responsible to co-ordinate corruption at the federal level. It is a patchwork or Swiss cheese [model] with lots of holes in it. The federal government needs…to develop a national anti-corruption policy.”

Another corruption professional said:

“Sentences are not enforced and the criminal system is not up to date to deal with long and complex corruption cases…police agencies must possess sufficient tools to battle corruption in an efficient manner.”

These findings reflect what we already know. Laws that sanction the crimes of the powerful are often poorly drafted and there are insufficient resources to ensure proper enforcement. Too many are willing to break the rules because they know governments will do little about it.

Neoliberalism and corruption

Our findings reveal that current anti-corruption efforts and debates often mask the role globalization plays in enabling corporate misconduct. The prevailing belief is that minimal government regulation is a good thing, as exemplified by Canada’s “one-for-one” rule that dictates if a new regulation is introduced, an existing one must be removed.

The role globalization plays in corruption, which originally led to demands for new laws in the first place, often gets lost in endless technocratic discussions about what laws are most effective for catching corporate cheats. This includes the OECD’s convention and their evaluations of Canada’s anti-bribery efforts.

In the 1980s, neoliberal economic doctrines swept through capitalist nations worldwide. Their central message was that maximum efficiency and productivity required that corporations be freed from government interference.

What followed was a period of unchecked globalization and massive privatization of public sector operations. Regulations were removed, regulatory agencies were downsized and funding was cut. Tariffs and currency restrictions were jettisoned, allowing corporations to expand their operations globally.

The surge in globalized free trade created mammoth increases in corporate wealth, size and power, and corresponding increases in inequality within and across nations. Many transnational corporations now have annual sales and profits greater than the GDP of nations.

Lasting effects of deregulation

The impact of neoliberal policies has been profound. The destruction of regulation, regulatory agencies and regulatory agents through downsizing, defunding and deregulation removed many of those responsible for passing and enforcing laws punishing corporate wrongdoing. While deregulation in the United States started with the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980, Donald Trump carried it to an extreme.

While successive Canadian governments have never directly copied their U.S. counterparts, we, too, have witnessed the negative outcomes associated with globalization.

Because multinational corporations have been allowed to grow so large and powerful, and are now so central to our economic and cultural lives, governments lack the ability to curb or punish their unlawful acts. As the SNC-Lavalin debacle illustrated, our governments frequently lack the motivation to do so as well.

Given all this, serious action against corruption, in Canada and abroad, must include moving beyond the narrow and reactive confines of bribery law and policy, as espoused by the OECD and woefully mishandled by the Canadian government, to confront the harms associated with globalization and bring multinational corporations under democratic control.![]()

Laureen Snider, Professor Emerita, Department of Sociology, Queen's University, Ontario; Jennifer Quaid, Associate Professor & Vice-Dean Research, Civil Law Section, Faculty of Law, L’Université d’Ottawa/University of Ottawa; Jon Frauley, Professor of Criminology, L’Université d’Ottawa/University of Ottawa, and Steven Bittle, Professor, Department of Criminology, L’Université d’Ottawa/University of Ottawa

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Grocery retailers are benefiting from food subsidies in Northern Canada

Saturday, 07 October 2023 08:18 Written by theconversationSoaring food prices, growing profit margins and record-high profits in the food industry have severely impacted the lives of many Canadians. According to Industry Minister François-Philippe Champagne, Canada’s largest grocery chains recently agreed to work with the federal government to stabilize prices.

But for Canadians living in remote northern communities, food affordability has been a crisis for decades. Grocery prices are routinely two to three times higher in Northern Canada.

These high food prices, combined with limited economic opportunities and high rates of poverty, have led to Northern Canada having the highest rates of food insecurity in the country. Almost half of all Nunavut households are moderately or seriously food insecure.

The federal government’s main policy to tackle this is a program called Nutrition North Canada that was launched in 2011. The program pays $131 million a year in subsidies to retailers based on the weight of eligible food they ship by air to communities without year-round surface transportation.

Subsidy rates vary based on the remoteness of communities as well as item type. For example, milk receives the highest subsidy, orange juice receives a lower subsidy and potato chips receive no subsidy.

Under the program, retailers sign an agreement promising to pass subsidies on to consumers in a process known as a “pass-through.” This means that if the government pays a retailer $1 to ship an item, the price of that item should be $1 lower for consumers.

However, residents of these communities have expressed concern that retailers may be taking advantage of them and using subsidies to increase their profits.

Insufficient accountability measures

To determine how much of the Nutrition North Canada subsidy was passed on to consumers, our recent study examined how much subsidy increases in October 2016 and January 2019 lowered food prices. We controlled for factors like food inflation, energy prices and high freight/operating costs.

We found that for every dollar paid to a retailer to reduce shipping costs, the prices paid by consumers fell by only 67 cents. When we considered communities with a single grocery retail store affected by the January 2019 subsidy increase, we found that an extra dollar paid to retailers reduced consumer prices by only 26 cents.

Our main finding — that the subsidy was not fully passed-through to consumers — remained unchanged when we considered only the most perishable goods, or accounted for economies of scale in shipping and other community characteristics.

Our findings indicate that Nutrition North Canada’s accountability measures are insufficient. Despite the publication of data on the subsidy and the price of a retail basket, and the existence of an auditing mechanism to ensure compliance with the program’s requirements, a substantial share of the subsidy is being captured by retailers.

The biggest retailer in the region — the North West Company — is a profitable, multi-billion dollar company that receives over half of the subsidy because these communities face far less competition than in the rest of Canada. According to the North West Company’s website, it “uses the entire amount of the subsidy to reduce retail prices for shoppers.”

Better addressing the problem

Why do existing accountability measures fail? First, it’s difficult to measure subsidy pass-through and retailer margins, especially with traditional audits. The contribution of retailer profits to high food prices today is still being debated.

Second, it may be even harder to punish retailers in this setting. A substantial share of the subsidy still goes to consumers, so punishing retailers by removing the subsidy would make food even more expensive.

How, then, can the federal government better address the problem of food affordability and insecurity in remote northern communities? Recent additions to the Nutrition North program, like the Harvester’s Support Grant, are a response to communities demanding more control over their food systems. This could involve subsidizing traditional hunting activities and funding community-led initiatives to support those in greatest need.

While these measures are promising, they are unlikely to replace the importance of store-bought food shipped by air. Measures to increase competition may help since retailers in these communities face far less competition than in the rest of Canada, but it’s still challenging for small, remote communities to have substantial competition.

While price controls and state-run stores (such as those in Greenland) could be worth exploring, they also have pros and cons that need to be carefully considered.

A simple and more market-friendly approach would require retailers to publish the price of all subsidized goods online. Greater transparency about food prices would help communities and their leaders hold retailers accountable in the court of public opinion, and make analyses like ours easier to conduct. While not a standalone solution for food affordability and insecurity in these communities, it could ensure more of our tax dollars go to support those in need.![]()

Nicholas Li, Assistant Professor, Department of Economics, Toronto Metropolitan University and Tracey Galloway, Associate Professor, Department of Anthropology, University of Toronto

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

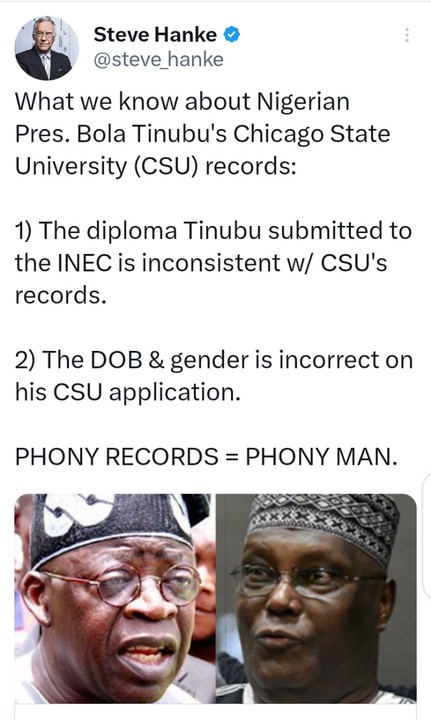

US Professor, Steve Hanke, Reacts To Tinubu's CSU Saga

Saturday, 07 October 2023 06:31 Written by ToriOntario’s Greenbelt is safe for now, but will the scandal alter Doug Ford’s course?

Monday, 02 October 2023 03:44 Written by theconversationMark Winfield, York University, Canada

Ontario Premier Doug Ford’s extraordinary reversal on his decision to open the Greater Toronto Area’s Greenbelt for housing development flows from two colossal political miscalculations.

The first was failing to recognize the Greenbelt, established by the previous Liberal government in 2005, had acquired an iconic status in the minds of residents of the region.

The Greenbelt was based on earlier Niagara Escarpment and Oak Ridges Moraine conservation plans, both adopted by Progressive Conservative governments. It was deeply embedded in municipal plans throughout the region.

Over time, the Greenbelt became a symbol in Ontario of efforts to protect prime farmland and key natural heritage sites from the region’s sprawling urban growth.

The government, however, refused to let go of the idea of opening the Greenbelt to development despite a complete lack of evidence that the land was required to meet the region’s housing needs.

According to the province’s integrity commissioner, it then allowed a “madcap process” to unfold around the actual removal of lands, which turned out to offer the potential for billions in profits to well-connected developers.

Ford’s future now in doubt?

The second blunder was to try to double down on the Greenbelt removal decision in the aftermath of harshly critical reports from both the province’s auditor general and integrity commissioner.

Even after the resignations of the housing minister and his chief of staff at the height of the scandal, Ford wouldn’t back down.

It took more than a month of a series of damning and embarrassing news reports — leading to the resignation of yet another cabinet minister, Public and Business Service Delivery Minister Kaleed Rasheed — for Ford to relent.

But the political damage suffered by the government through this period is starting to seem profound and the fallout is certain to continue:

- The RCMP is considering an investigation into the Greenbelt deal-making;

- Rasheed has admitted to misleading the integrity commissioner under oath during inquiries into the Greenbelt decision;

- The auditor general is planning a follow-up audit on the whole episode;

- Freedom-of-information requests from the media, and leaks from other sources, are likely to lead to further revelations in the weeks and months to come.

Although the next provincial election is nearly three years away, the Greenbelt scandal has raised serious questions about the viability of Ford’s own future as premier.

Greenbelt is out of the woods

Ironically, one almost certain outcome of the entire episode is that it’s probably ended any possibility of Ford’s intention to dismantle the Greenbelt.

The political fallout so far almost ensures no politician in Ontario will make similar moves against the Greenbelt for a generation or more.

The Greenbelt scandal has also vividly illustrated how badly the province has mishandled housing and development issues.

The province’s land-use planning system — including the Greenbelt and growth plans for the Greater Toronto Area — was once the subject of international acclaim for how it managed intense growth pressures while protecting farmland, housing affordability and natural heritage areas.

The Greenbelt debacle has demonstrated how that system had degenerated into an instrument wielded by the province to serve the wishes of well-connected developers.

Undoing the damage

A complete overhaul of the land-use planning system is now needed to undo the damage done by the Ford government, restore the system’s credibility and address the province’s housing needs effectively. Evidence backed by expert research, reason and basic democratic principles of transparency and accountability all need to be returned to the system.

Although the Greenbelt appears to be safe for the time being, attention now needs to turn to the government’s handling of the redevelopment of existing urban areas,

in his speech reversing the Greenbelt removals.So far the government’s approach to “transit-oriented communities” — ideally communities developed within a short distance of transit lines — has been to declare these areas free-for-all zones where the development industry can do as it wishes.

Predictably, the results of that approach in midtown and downtown Toronto, Richmond Hill, Markham and Mississauga have been an overwhelming focus on high-rise condominium developments, a lack of infrastructure and services of all forms, no mixing of uses (for example, significant new employment locations) or housing types, no attention paid to affordability and significant losses of existing affordable rental housing to “redevelopment.”

This is the polar opposite of the “complete communities” and urban development centres envisioned in the 2006 growth plan to guide urban redevelopment that accompanied the announcement of the Greenbelt.

Challenges ahead

The province has trampled on efforts by municipalities and communities to support more development along transit lines. The Ford government has apparently been intent on dismantling the growth plan as well as the Greenbelt.

The challenges facing the Greater Toronto Area are multi-dimensional and complex, including:

— Housing needs, particularly at the lower end of the income scale;

— Structural economic transitions and increasingly polarized labour markets;

— The impacts of a changing climate;

— A fiscal crisis, particularly for the city of Toronto, driven in large part by provincial downloading.

The Greenbelt fiasco has been an enormous distraction from these challenges — and it remains doubtful that the Ford government can significantly change its approach to governance to address them effectively.![]()

Mark Winfield, Professor, Environmental and Urban Change, York University, Canada

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Popular News

The fraught history of India and the Khalistan movement

Friday, 22 September 2023 06:06 Written by theconversationThe Indian government has warned its citizens living in Canada to exercise “extreme caution” due to a “deteriorating security environment” in the country.

The warning came after Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced that Canadian police were investigating “credible allegations” of the Indian government’s involvement in the killing of Hardeep Singh Nijjar.

On June 18, 2023, 46-year-old Nijjar, who migrated to Canada in 1997 and became a Canadian citizen in 2015, was shot dead by two masked gunmen in the parking lot of the Guru Nanak Sikh Gurdwara in Surrey, B.C.

The Indian government has denied any involvement, and as a result of the allegations, both countries have expelled diplomats from the other.

In late 2022, the Canadian government spoke of building a stronger partnership on the shared tradition of democracy between the two countries. But now, after a brief interlude of bonhomie, the Indo-Canadian relationship has reverted to a deep chill.

Canada correctly points out that the involvement of any foreign government in the killing of a Canadian citizen on Canadian soil is a violation of its sovereignty. India insists that Canada, particularly Trudeau’s Liberal government, has consistently ignored so-called terrorist activities against India by supporters of the Khalistan movement.

The Khalistan movement

The Sikh population in India is estimated to be about 22 million (1.7 per cent of the population), the majority of whom reside in the northern state of Punjab. The demand for a separate independent homeland for Sikhs — Khalistan — can be traced back to the 1940s when the British partitioned India and created Pakistan.

The movement was quiet until the 1970s, largely as a result of the Indian government dividing Punjab into a Punjabi speaking majority Sikh state (Punjab) and a Hindi-speaking state (Haryana) in 1966.

However, during the 1970s and 1980s, Punjab was engulfed in a violent political mass movement. Demand for a separate independent homeland was driven by the need to protect the Sikh religion and identity from the assimilationist policies of the Indian state, the need to address the rising unemployment in the agricultural community and Sikh youths.

The violence came to a head in June 1984. Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi ordered the army to storm the Golden Temple in the city of Amritsar, the most sacred and central pilgrimage site for Sikhs, where the leaders of the Khalistan movement had taken refuge.

After a week of fighting, not only was the temple desecrated, but more than 400 people were killed — including the leaders of the movement — and hundreds more were injured.

The Sikh community was deeply shocked both within and outside India. Just four months later, in October 1984, Gandhi was assassinated by two of her Sikh bodyguards. Her Congress party’s Hindu workers led anti-Sikh riots that killed thousands of Sikhs.

For the Sikh diaspora, many of whom left India after the riots, the suffering of their community has remained etched in their memories.

The Indian state has taken little action to convict those behind the violence against the Sikh community or to enter into a truth and reconciliation process with the community.

Khalistan activists killed

Nijjar’s murder is the third targeted killing of Khalistan leaders outside India.

In May, Paramjit Singh Panjwar, head of the Khalistan Commando Force, was shot dead by two identified gunmen in Lahore, Pakistan. In June, Avtar Singh Khanda of the U.K.-based Khalistan Liberation force was suspected of death by poisoning.

Nijjar was head of the Khalistan Tiger Force (KTF) as well as an active member of the United States-based group Sikhs for Justice (SFJ); both organizations are pursuing an independent Sikh homeland. Since 2022, SFJ has been conducting referendums in Canada and elsewhere in support of Khalistan.

In 2016, The Times of India reported that, according to intelligence officials in Punjab, Nijjar had taken over as the “operational head” of the KTF and was forming groups to launch attacks.

It also claimed that Nijjar frequently visited Pakistan and was in contact with Pakistani intelligence. There have also been allegations that Nijjar was running a camp near Mission, B.C., to carry out an attack in Punjab.

Mission Mayor Randy Hawes says that report is not credible. Ralph Goodale, then Canada’s public safety minister, would not comment at the time when asked if there was any basis to that allegation.

In an open letter to Trudeau, Nijjar pointed out that allegations against him were “factually baseless and fabricated.” He added:

“Because of my campaign for Sikh rights, it’s my belief that I have become a target of an Indian government media campaign to label my human rights campaign as ‘terrorist activities.’”

The Nijjar episode is the latest in the ongoing saga between India and Canada over the Khalistan movement. The Indian government claims that Canada’s failure to ban groups like KTF and SFJ compromises India’s sovereignty, territorial integrity and security.

Canada has so far refused to stop the referendums. Meanwhile, India’s current Hindu populist regime remains intolerant of any dissenting voices — especially from minority communities.![]()

Reeta Tremblay, Adjunct and Professor Emerita, University of Victoria

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Marching to Ottawa for neglected and murdered Indigenous men: One family’s fight for justice grows

Friday, 01 September 2023 03:27 Written by THECONVERSATION

Michelle Stewart, University of Regina

Summer in Canada means highways filled with tourists and travellers. For many summers now, some travellers move with a specific mission on those highways: to raise awareness about social issues facing Indigenous Peoples and the ongoing harmful impacts of Canada’s Indian Residential School program.

This summer, the Dubois family from the Pasqua First Nation in Saskatchewan is taking that walk. As they march from Regina to Ottawa, their hope is to raise awareness about the vulnerabilities and systemic inequalities faced by Indigenous boys, men and Two-Spirit People.

Specifically, the Dubois family is hoping to get some care and raise attention about what happened to two of their deceased family members. They are also demanding a national inquiry into missing, murdered and neglected Indigenous boys, men and Two-Spirit People.

My research focuses on racialized justice and settler colonialism. I first came to know the Dubois family in 2016 when Richelle was parked outside a Regina police station in -40 C weather demanding accountability in the investigation of her son’s death. We have since become friends and colleagues. I met up with the family as they began their walk.

Stories from fellow travelers

The cars leading the Dubois walk are covered with blue hand prints and photographs of deceased family members, Haven Dubois and Steven Dubois. The family’s march calls attention to the death of their loved ones, but also to all Indigenous people who face institutional neglect.

Constance Dubois, 59, is marching for her brother Steven who she says was mistreated at their local hospital in Regina. She also walks for her grandson, Haven, who she believes was murdered.

As they walk, the family has met many others on the road with similar stories.

Constance says the stories from fellow travellers have had a significant impact on her and her family: “The stories coming out while we are on the road makes us more determined to take their stories to Ottawa.”

Richelle Dubois, 42, is Haven’s mother. She says the stories have a common theme: “a lack of investigation and accountability.”

Haven Dubois, searching for justice

In 2015, Haven Dubois was 14 when he died. It was a school day and according to his school, he was on a school field trip. But instead he was found by his mother, unresponsive in a local shallow ravine in Regina.

According to his family, Haven was a strong swimmer.

The family believes Haven was murdered, and that his murder has not been investigated because it was prematurely deemed an accident. According to them, Haven had been subjected to gang recruitment and bullying prior to his death.

They see a flawed police investigation and modified coroner’s reports.

Intimidation and disrespectful care

After they rushed their son to the hospital, they say police declared their son’s death an accident before they left that day. Following his death, the Dubois family say they faced community intimidation and disrespect from police.

In the eight years since Haven’s death, the Dubois family has been fighting for a robust police investigation, exploring multiple mechanisms of police accountability. The family has seen two coroner’s reports, but believe they have not seen justice.

Just before they left on their walk, the Dubois family finally received a notice from the Saskatchewan coroner saying an inquest will be called in 2024 to investigate the circumstances of Haven’s death.

The inquest will focus on the cause of death, but will not look at how the investigation was originally handled.

The Dubois family feels they have demonstrated connections between other flawed investigations into the deaths of Indigenous people during the same time period.

Canadian-based sociologists Jerry Flores and Andrea Román Alfaro note the role between police inaction and settler colonialism and argue it is “through their (in)actions — what they say, tell, and do or do not do — that police affirm the disposability of Indigenous bodies, constraining the survival of Indigenous communities and consolidating settler colonialism.”

Steven Dubois, ‘ignored to death’

Steven Dubois, 47, was a partner and father of three when he died on Feb. 8, 2022.

His family believes Steven received substandard care at their local hospital. Steven had been previously diagnosed with a liver disease and the family says this diagnosis impacted his care.

Over the course of one week, they said Steven was taken by ambulance to the emergency room three times and was released back to his family despite being in medical distress. It was only when his family refused his return by ambulance and insisted that he receive medical care that he was admitted to the hospital.

Once there, the family says they received mixed messages about his care and how to manage his pain. Staff said Steven was alert and responsive, but it was clear to the family he was not — he was declining rapidly. Family members can only speculate had he been adequately cared for, he may have lived longer.

After his death, his partner, Amanda Snell, who had maintained diligent daily logs while Steven was in hospital, wrote to health care officials demanding information.

The correspondence she received indicate that Steven could have received medication as frequently as every 30 minutes to manage his pain, but he received it two to six times in a 24-hour cycle.

Amanda says the hospital confirmed hygiene protocols were not met.

His daughter, Avery Snell, said: “The very people who were meant to provide care and comfort made my dad endure excruciating pain…It is now our time to stand up and seek change for injustices that Indigenous families face every day in our society. Shame on our health systems.”

According to research, Steven’s story is one of many across Canada’s health-care system in which Indigenous people are subject to a “pattern of harm, neglect and death in hospitals.” Essentially, they are “ignored to death,” according to Manitoba law professor Brenda Gunn.

Rising voices

Critical theorist Sherene Razack writes that “although Indigenous people repeatedly register the connection between colonial violence and accountability, their voices are seldom heard.”

This summer, the Dubois family have added their voices to an increasingly large demand for further inquests by the Canadian government to continue to examine the impacts of colonial violence and racism on policing, justice and health-care practices.

The family’s next major town will be Sault St. Marie, Ont. They anticipate arriving in Ottawa by mid-September when they are hoping to meet with representatives from the Assembly of First Nations and the federal government. To find up-to-date details of their walk, visit their social media page.![]()

Michelle Stewart, Associate Professor of Gender, Religion and Critical Studies, University of Regina

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Trump out on bail – a criminal justice expert explains the system of cash bail

Friday, 01 September 2023 03:25 Written by THECONVERSATION

Megan T. Stevenson, University of Virginia

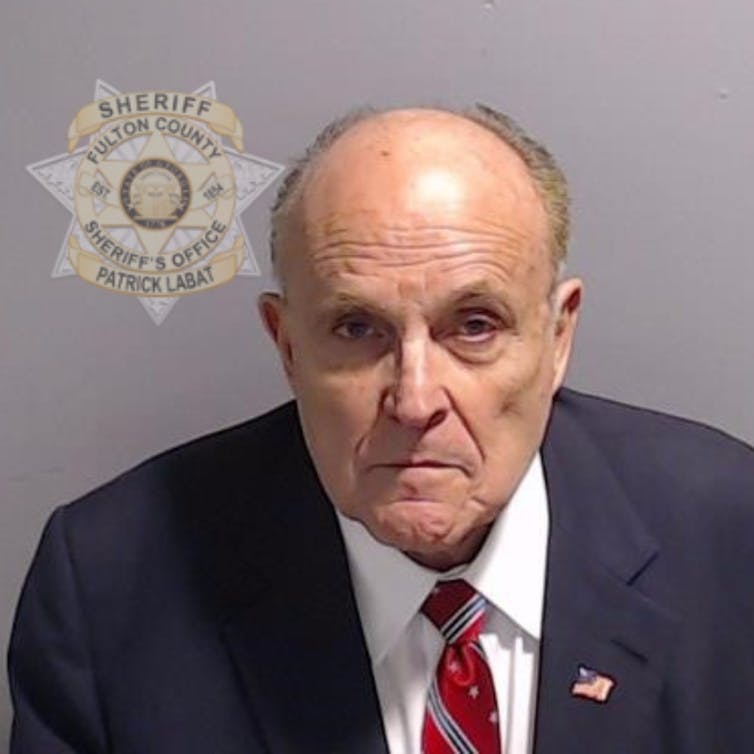

For several days, former President Donald Trump and his 18 co-defendants in a Georgia election interference case trickled into the Fulton County Jail in Atlanta to surrender for arrest, fingerprinting and mugshots before the noon Aug. 25, 2023, deadline. Charged in the same alleged conspiracy to overturn results in Georgia’s 2020 presidential election, the defendants did not draw the same bail agreements or amounts.

Trump’s bail was set at US$200,000, while his former attorney Rudy Giuliani’s bail was set at $150,000. Meanwhile, attorneys John Eastman, Kenneth Chesebro, Jenna Ellis and Sidney Powell each had bail set at $100,000. Bail for other co-defendants ranged from $10,000 to $75,000.

The Conversation asked Megan T. Stevenson, a University of Virginia law professor who researches bail, to answer questions about the American bail system and how the bail amounts in the Georgia election interference case reflect that system.

What is the purpose of the cash bail system, and how does it work?

Cash bail is when the defendant must pay money before being released from jail after arrest. The money can come from the defendant’s savings, from a friend or family member, or be borrowed from a bail bondsman. The words bail and bond are often used interchangeably.

The idea behind cash bail is that it provides a financial incentive to deter misconduct. If a defendant flees or otherwise misbehaves, they forfeit their bail amount.

After someone is arrested, they are seen by a judge or magistrate who sets bail. The bail hearing is usually exceedingly short – a few minutes at most. Sometimes, the hearings happen by video conference.

Most defendants do not have defense counsel at the time of the bail hearing, but if they do, the defense counsel can argue for lenient bail amounts and conditions.

While bail laws vary from state to state, bail is usually supposed to be set at the minimal amount of money that will ensure the defendant appears in court and doesn’t violate court orders. For instance, one of the conditions of Trump’s bail is that he cannot intimidate witnesses, co-defendants or other people – including on social media. If Trump violates this condition, he is at risk of having his bond revoked and being placed in jail.

What’s the history of bail in the US?

Bail has been a part of the American criminal justice system since Colonial times. Originally, when a criminal defendant was released on bail, it meant they were released into the supervision of someone who had vouched for them. The defendant would be required to pay a certain amount of money if they failed to subsequently appear in court. But no one needed to pay any money up front. Over time, that has changed. Now, most defendants are expected to pay cash bail before they are released, and a surety – a person who vouchers for the defendant and promises to supervise them – is generally not required.

Some criminal justice reformers have objected to the cash bail system. Why is that?

In the U.S., people are presumed innocent until proved guilty in court. Being jailed prior to trial is supposed to be a “carefully limited exception” as established by Supreme Court precedent.

But that reflects theory better than practice. Approximately 20% of the imprisoned population in the U.S. consists of people awaiting trial.

For reference, there are more people detained pretrial than are serving time due to a drug sentence. And almost all of those detained had cash bail set and would have been released if they could afford it.

Some detained people are facing very serious charges and had very high bail. But many are detained on relatively low bail amounts that are simply beyond reach for the poor to pay.

Theoretically, the ability to pay bail is supposed to be taken into account, but judges frequently don’t. The result is that people end up behind bars before trial simply because they are accused of a crime and they are poor, which is both a violation of equal protection and a waste of taxpayer resources.

The bail reform movement is trying to ensure that the only people detained before trial are people who pose a specific threat of serious crime if they are released. Illinois, for example, eliminated its cash bail system, making all defendants eligible for release before trial. In other jurisdictions, nonprofit bail funds pay bail for the poor, with the goal of ensuring that nobody is jailed due to inability to pay.

Is it customary for people who are charged with the same crime to get different bail amounts?

Yes. Trump and his co-defendants have been charged in a conspiracy. But conspiracy law is very sweeping and can range from central players in the crime to those with very minor roles. When setting bail, judges take into account the seriousness of the alleged criminal activity, the criminal record and any other information that pertains to the likelihood that the defendant will flee, intimidate witnesses or commit a new crime. Given the wide variety of roles Trump and his co-defendants allegedly played, as well as these other varying circumstances, it’s not surprising that their bail would differ.

Is there research that examines whether bail is granted to demographic groups differently?

Studies show that racial bias and racial disparities in bail exist, and they arise from various sources. First, a defendant’s criminal record plays a big role in the bail amount. If defendants from disadvantaged groups are more likely to be arrested than others who have committed the same crime, then they will have longer criminal records and will get higher bail amounts. For instance, numerous studies show that Black people use and sell drugs at similar rates to white people, but are much more likely to be arrested and convicted for drug crimes. So, Black people in the criminal justice system often have longer criminal records than white people in the system.

Also, a judge’s beliefs about the likelihood that someone will commit a crime in the future can be influenced by stereotypes about race and criminality. These stereotypes can lead a judge to set bail higher for Black defendants who pose the same risk level as white defendants.

Finally, poor people will be less able to afford a certain bail amount than those with greater wealth. And since poverty is strongly correlated with race, Black and Hispanic defendants are often detained at disproportionate rates.![]()

Megan T. Stevenson, Professor of Law, University of Virginia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

To reduce rising crime rates, Canada needs to invest more in social services

Sunday, 27 August 2023 03:48 Written by THECONVERSATION

Martin Andresen, Simon Fraser University

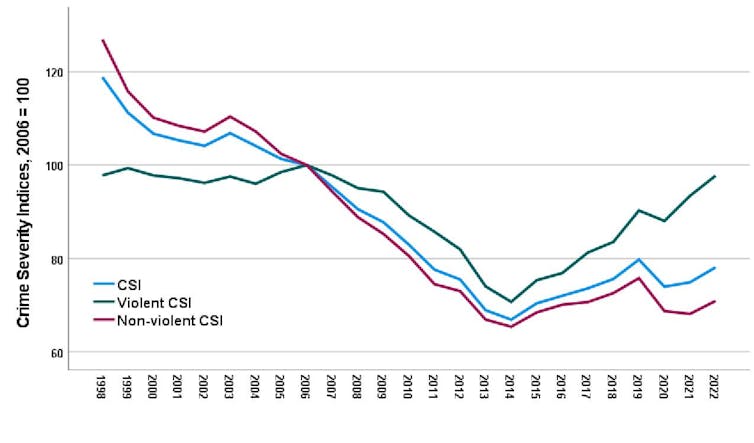

Every summer, Statistics Canada releases crime rate and crime severity data for the previous year. This year, Canada’s Crime Severity Index (CSI) increased by 4.3 per cent, the violent CSI increased by 4.6 per cent, and the non-violent CSI increased by 4.1 per cent. Moreover, aside from a drop during the COVID-19 pandemic, these indices have been on the rise since 2014.

An April 2023 poll found that 65 per cent of Canadians felt crime has gotten worse compared to before the pandemic. Conservative Party leader Pierre Poilievre has criticized the Liberal government for the rising crime figures in recent months.

Canada’s new justice minister, Arif Virani, said it was empirically unlikely that Canadians are less safe, but that the government would act to address feelings of growing insecurity.

But what is the CSI and what do changes in crime stats mean for Canadians?

What is the Crime Severity Index?

The CSI was introduced in 2009 and represented the first major change in measuring crime in Canada since the 1960s. Its purpose was to identify changes in the seriousness or severity of crime reported to the police.

The CSI is calculated like a crime rate, but different crimes are given a different weight, or importance, based on their severity. Without this kind of system, a community that has 10 low-level assaults will have the same violent crime rate as another that has 10 homicides because each incident would be given the same weight.

The CSI accounts for this by using different weights for different crime types: approximately 80 for assault level 1, 7,000 for homicide and one for gambling. These weights are based on sentencing decisions in the court system.

Understanding the data

At first glance, the CSI is great because it allows us to determine which areas experience more violence. However, there are at least three issues when considering what changes in the CSI mean for most Canadians.

First, the CSI must be considered over longer periods of time than year-to-year fluctuations. We now have the CSI for 1998-2022, 25 years of data. Yes, the CSI has been increasing since 2014, but it is still much lower than it was 25 years ago.

Crime has been falling around the world, including Canada, since about 1990. It may be the case that 2014, for Canada, was just the low point for crime. Because of this, relatively small changes in incidents will have large percentage changes.

Second, because the CSI is calculated in a similar fashion to crime rates, places with lower populations will be “punished” by the CSI. For example, in a city of one million people, one homicide will lead to a homicide rate of 0.1 per 100,000 people. However, in a city of 15,000 people, one homicide will lead to a rate of 6.67 per 100,000 people.

Now if you add in the weights used in the CSI, this disparity becomes magnified. To be clear, the math is not wrong — it is just that the statistic has its limitations. The CSI is fine for Canada, its provinces and larger metropolitan centres. But, for the rest of the country, the CSI should be interpreted with caution.

Third, crime is usually concentrated in specific areas. Across the world, including Canada, one-half of crime reported to the police occurs in approximately five per cent of the city. These places are, generally speaking, areas that experience more poverty, mental health and addiction problems, and other social challenges.

In short, those who are already suffering most, especially post-pandemic, are being victimized more with these increases in crime in Canada; this has been shown in Vancouver and Saskatoon.

Reducing crime

What should our takeaway be here? We need to be careful of how we interpret the CSI. Crime has been increasing the past eight years: homicide, sexual assault, assault (particularly with a weapon) and vehicle theft are all increasing more than average. So, despite my caveats, crime has been increasing of late, particularly violent crimes.

The notable common thread in all of the media coverage of these violent attacks is the presence of mental health issues, addiction, homelessness and poverty. How did we get here? Over the past 40 years, conservative governments have defunded social programs and social services.

A result of these changes has been a decrease in social welfare and increases in social ills. Where we are today is the result of a 40-year process that we cannot expect to reverse in short order. We need to reinvest in social programs and services, knowing it will take time to see an impact.

Putting government funding back into social services is a large component of the Defund the Police movement. Rather than continuing to spend on reactive models such as policing that do little more than criminalize poverty and disadvantage, we need to reinvest in preventive strategies that actually work.

To prevent crime, governments need to invest more in existing social welfare programs and reestablish social services such as basic income.

This spending on social welfare services and basic income should be viewed positively across the political spectrum as well. The provision of basic income and social services would both support vulnerable populations and be cost-effective.

If we are concerned about crime and its severity, we should support reinvesting public funds into preventative strategies such as housing, mental health care, basic income and addiction services.![]()

Martin Andresen, Professor of Criminology, Simon Fraser University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.