Klaus Meyer, Western University

Canada needs modern transportation infrastructure to enable sustainable mobility. This infrastructure has to meet new demands for energy efficiency and emission standards while serving denser urban populations.

Ideally, Canadian businesses ought to play a leading role in designing, building and operating such infrastructure, both in Canada and around the world.

However, Canada isn’t doing well on this front. Sustainable infrastructure investments have been neglected, rail transport export surpluses have turned to deficits and Canada’s leading transport company, Bombardier, is expected to sell the country’s largest rail business to French firm Alstom.

To turn this negative trend around, Canada needs to promote transport technology businesses, supported by a stable, predictable policy framework for sustainable infrastructure.

Growing deficit

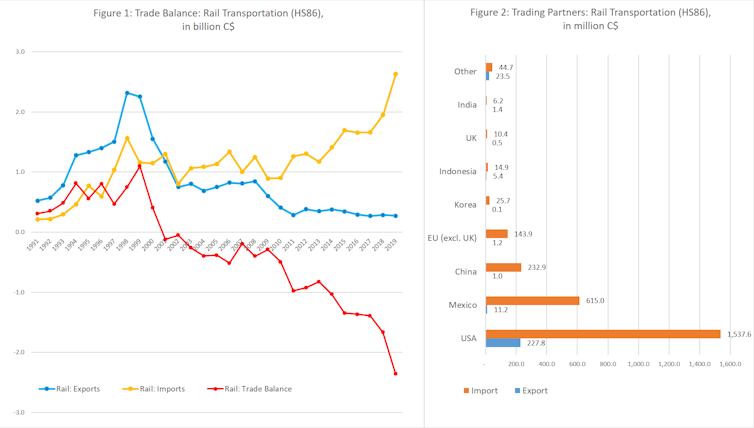

Canada had a solid trade surplus in rail transport in the 1990s. But this has turned into a continuously growing deficit over the past 20 years, reaching $2.4 billion in 2019 (see Figure 1 in the graphic below).

The only major market for Canadian rail equipment is the United States, but even in that bilateral relationship, Canadian exports of $228 million are swamped by imports of $1.5 billion (Figure 2).

Canada has literally transformed from a rail transport leader to a laggard in two decades.

This trend is closely associated with Bombardier. The Québec company has, since the 1970s, become one of the biggest players worldwide in rail transport. However, this growth was achieved by acquisitions around the world, not by growing businesses in Canada. Consequently, the international hub for its transport unit is now in Europe, with global headquarters in Berlin.

At the same time, Bombardier’s technology failed to stay cutting edge. Recently, the company has been in the news due to complaints about major quality-control problems from subway operators in Toronto, London and New York as well as from the the German national rail operator.

Toward carbon-neutral transit

As climate change challenges Canada to become more energy-efficient and carbon-neutral, transportation has to make its contribution. That means infrastructure investments need to address not only today’s needs, but the needs of society in 10 years as investments tend to create lock-in effects for several decades.

In other words, today’s investments need to cater to tomorrow’s needs, when society has a higher urban density and is no longer able to ignore the environmental impact of its mobility choices.

For urban mobility, any choice is better than single-occupancy commuter cars. Cities of the future require different types of urban transport systems such as subways, trams and bike paths.

Read more: Build it and they will ride: Bicycle geography lessons for Toronto

For medium distances, air travel also needs to be replaced by more energy-efficient models, such as high-speed rail.

With increasing urbanization, especially along the Windsor–Toronto–Montréal-Québec City corridor, the suitability of alternative modes of transport is changing. Cars may be appropriate for isolated rural communities, but less so for metropolitan areas with hundreds of thousands of people.

In recent decades, Canadian infrastructure dollars have poured into roads and airports, neglecting passenger rail travel within and between urban centres. Canada is consequently facing an infrastructure gap compared to other industrialized economies.

Progress is slow

On the one hand, municipalities like Kitchener-Waterloo, Toronto and Gatineau are moving forward with urban transit schemes, although they’re modest at best compared to developments in Europe and Asia. Other cities like Vancouver are struggling to raise funds.

On the other hand, the 2020 transport plan by the Ontario government prioritizes road transport, discontinues already advanced plans for high-speed rail and offers only token projects for sustainable urban transit.

In 2019, Sweden and Germany saw a decline in domestic flights and an increase in long-distance train travel, a consequence at least in part of raised climate awareness. In Canada, most people lack such choices because mid-range rail transport is slow, infrequent and requires advance booking.

At the same time, Canadian industry needs domestic infrastructure to move products for export. That’s a high priority in view of Canada’s policy objectives to diversify exports away from the United States, which currently accounts for 73 per cent of exports.

Investing in infrastructure and technology

What would it take for Canada to become a leader in sustainable mobility?

Canada is promoting an image of itself to the world as environmentally responsible and concerned about climate change. At the same time, Canada has a highly educated workforce with capabilities to develop cutting-edge technologies. That means Canada should have a strong foundation to develop sustainable mobility systems.

So what’s missing?

First, Canada needs to invest in skills and technologies. Developing mass transport is technology intensive, requires systems management knowledge and software that ensures that trains run frequently, speedily and on time. A well-managed system, for example, doesn’t grind to a halt when there’s a disruption hundreds of kilometres away, as happened recently in southwest Ontario.

The private sector has to lead. With its focus now on business jets, Bombardier is unlikely to play a role in sustainable mobility. This creates both opportunity and need for Canadian technology entrepreneurs to fill the void.

A predictable policy framework

Second, the industry needs predictable domestic demand for for high-quality transport products and services.

For infrastructure businesses, demand is tied to government regulations and public sector investments, both nationally and locally. Governments investing in infrastructure must insist upon the highest quality, not only to deliver value for money for Canada’s travelling and commuting public, but also to induce businesses to develop products that can succeed internationally.

And governments must make long-term commitments, because infrastructure projects take years if not decades to complete. For businesses to invest in new capabilities, they need predictable demand. No one will commit to projects that may be cancelled after the next election.

Building infrastructure takes time. Sustainable mobility systems require persistent investment in high-quality infrastructure that will enable Canadians to make environmentally friendly travel choices in the future.![]()

Klaus Meyer, Professor of International Business, Western University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.