Olayinka Ajala, University of York

During the last general elections Nigeria in 2019, about 28 million of the 84 million registered voters filed out to elect the president, vice president and members of the national assembly.

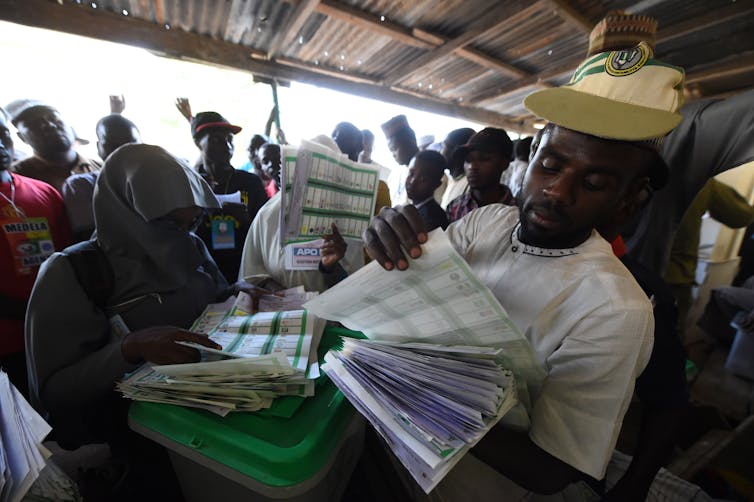

In addition to security concerns in some areas, allegations of rigging and the generally tense atmosphere in several states, the other major issue that bogged the electoral process was voters’ complaints about the long ballot paper which had to accommodate 73 presidential aspirants. And there were 91 political parties presenting candidates at the national, state and local government elections on the ballot.

Voters complained about how difficult it was to locate their preferred choice because ballot papers carried the names and logos of all the political parties, some with similar acronyms. Some voters also noted that they spent a long time voting, sometimes resulting in mistakes and eventually invalid votes.

Since the election a year ago, there has been a growing clamour for reform. In response, the Independent National Electoral Commission recently announced the de-registration of 74 out of the 92 registered political parties in the country. The electoral umpire based its decision on the provision of the 1999 Nigerian constitution as amended in 2018, which, it says, empowers it to de-register political parties.

This suggests that reducing the number of parties is an important step in streamlining Nigeria’s electoral system. But the actions of the electoral commission might not be enough to solve some deeper systemic issues facing the country’s electoral processes which result in the abuse of the system.

The drivers

Since the country returned to democracy in 1999, floating a political party is sometimes viewed as a “business venture”. This is for two main reasons.

First, the Independent National Electoral Commission provides funding to political parties. Section 228c of the Nigerian constitution allows for the disbursement of annual grants to political parties to assist them in discharging their functions.

For instance, ahead of the 2003 general elections, the electoral commission disbursed N420 million to seven political parties including the People’s Democratic Party at an average of N60 million per party.

Problem is, the money is often difficult to account for. This is in spite of the fact that the electoral commission is expected to audit the account of registered political parties.

Second, nobody can stand in an election in Nigeria unless they’re attached to a political party. What this means is that parties sell nomination forms to any candidate who wants to contest under their banner. This system has led to a situation in which application forms to contest electoral positions are believed to be one of the most expensive in the world. Some parties charge more than N25 million ($69,000) for the purchase of presidential nomination forms. This encourages corruption as would-be politicians try and rustle up the money.

Different schools of thoughts

There isn’t unanimity among Nigerians about the problem. Opinions about the number of political parties are often split along at least three main lines.

The first group argues that the number of political parties in the country is an indication of the strength of its democracy. The basis of this argument is that more political parties result in more participation.

A second group believes that many parties are formed only for personal aggrandisement and not in the interest of the electorate. They don’t believe they’re electable and are quick to form alliances to support larger parties. This is usually done closer to elections and often after personal benefits in form of cash rewards or promise of political patronage have been promised.

A third group argues that some of the political parties are too small to have any national significance or the resources to reach out to over 200 million Nigerians. This argument has it that they should either merge with other parties or be deregistered. The electoral umpire falls under this category.

The electoral act sets down certain conditions under which parties can be deregistered. It was on the basis of these that the electoral commission deregistered 74 political parties. Its chairman argued that most of them could not garner up to 20,000 votes in the last presidential elections and, thereby, fell short of the electoral Act. The decision has been challenged in court by some of the affected parties.

Lastly, there is the issue of voter apathy. Millions of Nigerians stayed away from the polls in the last election.

What to do

A survey of Nigerians showed that voters were pleased with the step taken by the electoral commission. But not everybody was happy. Some, including party leaders, kicked back against the action stating that it posed a threat to the country’s democracy.

The bigger question is whether the commission’s decision will solve the abuse of the country’s electoral system. I believe not. This is because the criteria for the registration of political parties remain loose and there are over 100 pending applications. The criteria for the registration of political parties must be clarified and tightened to prevent politicians from continuing to use political parties for their personal gain.

In addition, the electoral commission needs to address three key issues. First, it must stop the payment of annual grants to political parties. This would allow parties to find sustainable means of funding themselves. One avenue could be through party membership contributions.

Second, the commission must put a cap on the prices of nomination forms for electoral positions.

Third, there is a need to criminalise the “cash for stepping down” practice, whereby larger parties induce smaller ones with cash incentives and political patronage during the election cycle.

Deregistering political parties will only lead to registration of new parties by the same people if these key issues are not addressed.![]()

Olayinka Ajala, Associate Lecturer and Conflict Analyst, University of York

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.