Maria Nugent, Australian National University and Gaye Sculthorpe, The British Museum

Captain James Cook arrived in the Pacific 250 years ago, triggering British colonisation of the region. We’re asking researchers to reflect on what happened and how it shapes us today. You can see other stories in the series here and an interactive here.

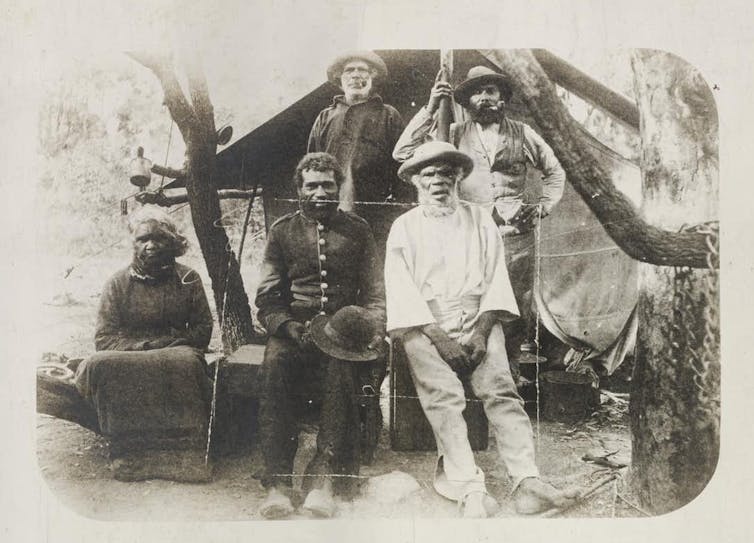

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article contains names and images of deceased people.

In the early Sydney colony, newcomers commonly quizzed Indigenous locals about their memories of Captain Cook and the Endeavour.

They believed the arrival of a shipload of British men who stayed for a week was an incredibly memorable event; and assumed that details of it would have been preserved — even treasured — over time.

The accounts given are hardly ever a straightforward recounting of what Cook did. And they rarely tally with what is recorded in the voyage accounts.

Rather, they carry those common qualities of remembering: telescoping, conflating, rearranging time, stripping back detail, and upping symbolism and metaphor. Unpicking the threads of these memories is vital for historians wanting to find agreement on details and interpretations, and provenance of items that changed hands during early encounters.

Recollecting memories

Some oral accounts were written down – either at the time they were heard or later. Records reveal accounts extracted out of curiosity, to assist with commemorations, or simply to pass the time.

One account comes from the early 1830s. Two priests stationed at St Mary’s Cathedral near Sydney’s Domain met an Aboriginal man from Botany Bay. They asked him “if he had any recollections of the landing of Captain Cook”? He was born too late to have witnessed it himself, but he shared a reasonably long story he had inherited from his father, the recollection of which one of the priests later published.

Similarly, in a recent prize-winning essay, historian Grace Karskens reconstructs a tantalising conversation between Aboriginal woman Nah Doongh and her settler friend Sarah Shand.

“Shand was intensely curious about Nah Doongh’s memory of her first contact with white people”, Karsken explains, but was frustratingly incapable of seeing she was implicated in the dispossession of Aboriginal people, including Nah Doongh.

Nah Doongh offered her a story about Cook, whom she presented as big and evil, violent and greedy, in a way that anticipates late 20th-century Aboriginal oral narratives.

Cook emerged as an erstwhile topic in cross-cultural conversations across colonial Sydney, but the substance of what was said and why was less dependent on the details of what Cook and his crew had done in 1770 than on the conditions, contexts and purposes of the chats.

As many have noted, discourses about Cook in Australia are neverending; but their contours and emphases change in relation to – and contribute to change in — broader Australian culture and politics.

Who is speaking?

Sometimes it is not the account given of Cook that is of primary interest, but the identity of the narrator.

Dharawal woman Biddy Giles lived around the Botany Bay area for much of the 19th century. An account she gave of Cook’s landing was written down after her death by a white settler.

He recalled she’d said: “They all run away; two fellows stand; Cook shot them in the legs; and they run away too!”.

This economical account is faithful to longer Endeavour voyage renditions. But researchers are more exercised by biographical information showing Giles was briefly married to a much older man, Cooman. Speculation swirls that Cooman’s grandfather, also called Cooman, was one of the two fellows shot.

When historian Heather Goodall in her book Rivers and Resilience returned to Giles’ life, she made it clear she thought historians who relied on documentary sources should not attempt such jumps.

Repatriation requests

Not all researchers have been so circumspect. In 2016, speculations about the identity of one of the two men shot contributed to formal requests to museums in Britain for the return of artefacts either known to have been collected at Botany Bay during the Endeavour voyage (four spears at the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Cambridge) or believed to have been (a shield at the British Museum in London).

The repatriation claim repeated historian Keith Vincent Smith’s assertion one of the two men was Cooman.

When asked for advice on this repatriation request, I (Nugent) concluded there was no consensus about that assertion, noting it was unfortunate that:

historical claims which derive from inconclusive evidence, are based on questionable interpretative leaps, and are not presented in ways that recognise and respect the complexities of writing “early contact” history from fragmentary sources […] were being relied upon.

Other arguments would serve applications for return far better.

The request was unsuccessful, but the process was productive and generally positive. More work has taken place since, both further historical research and object analysis, and importantly, renewed and enriched relationship-building.

Building a material history

Retracing the speculative leaps made between the historical encounters, collected objects, and related written, oral and visual sources reinforces the urgent need for well-resourced, critically reflexive, and multimodal methods of interpretation. This is particularly true when the return of an object and the knowledge it embodies is strongly desired.

This year we will commence a new ARC-funded project, Mobilising Objects to draw together objects in international collections, images, written records, oral accounts, and contemporary expertise to generate a material history of early colonial Sydney.

The project aims to build knowledge about exceptional, but poorly-documented, Aboriginal objects from Sydney and the NSW coast (circa 1770-1920s) in British and European museums. We hope to build strong relations between Aboriginal communities and overseas museums and lay robust foundations for future projects seeking the return of Indigenous cultural heritage.

Gathering together records of oral accounts given by Aboriginal people about Cook and other seaborne interlopers, and grappling with the interpretive challenges they present, will be a vital aspect of this work.

Maria Nugent, Co-Director, Australian Centre for Indigenous History, Australian National University and Gaye Sculthorpe, Curator & Section Head, Oceania, The British Museum

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.