USA & CANADA (901)

Latest News

New Jersey Gang Member Sentenced to Life for Killing Nigerian Man Who was Urinating in his Street

Friday, 21 February 2020 02:08 Written by thestreetjournal.orgA New Jersey gang member has been sentenced to life in prison for shooting dead a Nigerian man who he saw urinating in his street.

Bloods member Christopher Poole “executed” photographer Rasheed “O.J.” Olabode, 27, by shooting him in the heart as he begged for mercy.

Christopher had seen Olabode easing himself behind a car in Newark in April 2018 so he confronted him. Surveillance video showed Olabode begging to be spared, but Poole “executed” him anyway, prosecutors said.

“The only mistake that appears the victim made was going to relieve himself in front of the wrong person,” prosecutor Jason Goldberg told Superior Court of Essex County, NJ.com said.

“And that simple, simple act — something that every single person does, every single day — was enough in the eyes of Mr. Poole to execute a man, shoot him in the heart as he prayed and tried talking his way out of it.”

Poole — who has a tattoo on his throat of a hand giving the middle finger — has a lengthy rap sheet starting from when he was just 15.

Superior Court Judge Ronald Wigler noted his “utter lack of remorse” for the execution in front of two of the victim’s friends.

Wigler, who has served as a Superior Court judge for a decade, said: “This was certainly one of the most — if not the most — senseless murder cases that I have presided over and been involved with.”

On Tuesday, February 4, Poole was sentenced to life in prison for first-degree murder. He was also sentenced to 10 years in prison for one weapons offence that will run concurrently.

He must serve at least 63 years before he is eligible for parole under the state’s No Early Release Act.

One of Poole’s two sisters cried and fled the court when he was sentenced. “I know his heart. I know that this isn’t the person that he wanted to become,” she said.

Olabode was originally from Nigeria. His family could not afford to make it to New Jersey for the sentencing, the court heard.

On Family Day, let's expand our definition of family to reflect our realities

Saturday, 15 February 2020 14:49 Written by theconversation

Hilary Rose, Concordia University and Shannon Hebblethwaite, Concordia University

Monday, Feb. 17 is Family Day in parts of Canada. Started in Alberta in 1990, four additional provinces now celebrate Family Day on the third Monday in February: British Columbia, Saskatchewan, Ontario and New Brunswick. (Other provinces have holidays reflecting their heritage.)

Québec is one of few jurisdictions that does not have a civic holiday in February, though the province has generous family leave policies.

This year, to coincide with the emphasis on family, Concordia University and the Vanier Institute of the Family are hosting a conference on families and family life on Feb. 20. The conference will explore some of the tensions and dichotomies embedded in families. For one, how do we define what family means?

Expanding the definition of family

How we define family (and who gets to do that defining) is an important starting point for conversations on family life. Who’s in? Who’s out? Who actually counts as family? For some, family means married parents with children, or married heterosexual parents with children. For others, it may mean a chosen family, or a cohabiting couple with no children.

For our conference, we are using an adaptation of the Vanier Institute’s definition: a family consists of any combination of two or more people, bound together over time, by ties of mutual consent and/or birth, adoption or placement, and who take responsibility for various activities of daily living, including love.

Our research has identified the need to attend to extended families, including grandparents, aunts and uncles. It also includes the need to extend the definition of family to non-traditional family forms including LGBTQ2S+ families, chosen families, multi-generation families that include grandparents, single parents and people living alone.

It wasn’t until 2001 that Statistics Canada gathered information on multi-generational households, and in 2011 the census first counted stepfamilies and foster children. Families in Canada are diverse and our programs and policies should be responsive to this diversity.

We find that a narrow definition of family can neglect the experiences of single-parent, poor and minority families. For example, research shows that women of colour and low-income women often experience and interpret motherhood differently than white, class-privileged mothers.

Recently, researchers began to examine how diversity related to race, class and sexual orientation affects grandparent-grandchild relationships. To continue to expand our understanding of families’ experiences, we need to think more broadly about what factors matter in families.

Family realities should be reflected in policy

How we define family impacts social policy like parental, maternity and paternity leave entitlements and child-care tax credits. Caregiver benefits and compassionate leave policies are also tied to family status. Eligibility depends on whether you are a family member.

In health-care contexts, visitors in intensive care units and emergency departments are often restricted to immediate family and grandparents often don’t have rights when it comes to child custody cases. So a comprehensive definition of family influences how we develop programs for families and who is eligible.

Besides needing to expand the definition of family, we also need to look at the messy realities of family and family life. The irony of organizing a public family conference while attending to the realities of our private family lives was not lost on us. As we scheduled meetings and conference calls, we were also planning Skype dates, making school lunches and caring for parents across the country.

We believe that practitioners, service providers and policy-makers need to take into account the complexity of family lives when thinking about family practice, programs and policies. Family scholars and the Vanier Institute of the Family refer to using a family lens: needing to look at the complexity of family and family relations beyond individual family members.

Thinking about families in a broad sense when we develop programs and policies can be challenging. It is much easier to use an individual lens to think about developing children, or aging seniors. But these individual family members, even those who live on their own, live out their lives in the context of families —whether biological or social.

The future of families

When using a family lens, it can be easy to slip into a glass-half-empty approach. Family life educators and social workers struggle with the tension between deficit models of family, and asset or strength-based models of family. Instead of only focusing on what problems families experience, we can benefit from understanding what strengths they have and what makes them resilient in the face of life’s challenges.

Some family practitioners and family scholars would say that in the best of all possible worlds, it would be preferable to remain apolitical as we think about family and as we provide information and assistance to families.

And yet, some of us feel strongly that it is important to look beyond families to society to advocate on behalf of families, or family members, who are at risk.

At our families conference we will be exploring the tension between present and future. Based on our understanding of systems and systemic change, we will emphasize envisioning a different future by including all families — in the broadest sense.

Rather than staying focused on the present, we look towards a future of change by asking the question: “Wouldn’t it be great if …?”![]()

Hilary Rose, Associate Professor of Applied Human Sciences, Concordia University and Shannon Hebblethwaite, Associate Professor of Applied Human Sciences, Concordia University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

US visa ban: Visa suspension only on ‘immigrant visa’ not on business, students, others – Presidency

Sunday, 02 February 2020 13:11 Written by OASESNEWSTHE NIGERIAN government said the United States visa restrictions on Nigeria only apply to ‘immigrant visas’ and does not affect official, business, tourism and student visas.

According to a statement signed by Femi Adesina, a special media aide to the Nigerian President, Muhammadu Buhari, he wrote on Saturday that the suspension would take effect on February 21st, 2020.

“For Nigeria, the restriction is the suspension of the issuance of “immigrant visas” to Nigerian passport holders only. This suspension shall come into effect on 21st February 2020. The suspension does not apply to other U.S visas such as those for official, business, tourism and student travel,” he wrote.

Adesina explained that the travel ban became necessary following the failure of Nigeria to meet up with the performance ratio adopted by the US on security.

“The DHS states the suspension of “immigrant visas” became necessary following a review and update of the methodology (performance metrics) adopted by the U.S Government to assess compliance of certain security criteria by foreign governments. This resulted in certain enhancements on how information is shared between Nigeria and the U.S” he explained.

The statement further read that Nigeria is committed to maintaining a good relationship between the US and other international allies.

“Nigeria remains committed to maintaining productive relations with the United States and its international allies especially on matters of global security”.

As a result of the ban, Adesina noted that Buhari has set up a committee chaired by the minister of interior, Rauf Aregbesola to look into the metrics as stipulated by the US.

Statement from the White House reads:

“As set forth in Presidential Proclamation 9645, countries that fail to conduct proper identity management protocols and procedures, or that fail to provide information necessary to comply with basic national security requirements—including sharing terrorist, criminal, or other identity information—face the risk of restrictions and limitations on the entry of their nationals into the United States.”

Curious Kids: Do teachers get paid when they go on strike?

Tuesday, 28 January 2020 05:11 Written by theconversation

Charles Ungerleider, University of British Columbia

Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. Have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Send it to This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Do teachers get paid when they go on strike? — Zara, 10, Toronto.

Many people are confused about whether teachers get paid their salaries during a strike. The short answer is that they don’t.

But striking teachers often receive a bit of financial help during a strike from money they themselves have already paid to their unions. In other words, teachers are paying themselves when they strike.

On strike

When employees strike they refuse to perform their normal duties because they have a strong complaint about how the employer is treating them.

The employer, in this case, is the school board — a group of schools in a particular region.

Teachers may be striking because the school board wants to put more students in the classes they teach, or teachers feel the school board is not paying them enough money for their work.

In other words, a strike is a sacrifice that teachers make today to improve things tomorrow.

How can you pay yourself?

When teachers get paid for their work, a very small portion of the money they earned goes into what’s called a teachers’ union — a big group of teachers who share common professional interests.

My involvement with unions has shown me that negotiating as a group of workers (a union) with an employer (a school board, for example) for wages, working conditions and benefits protects individual workers from being treated unfairly by an employer.

I was a union member when I was a teacher and when I’ve held other jobs. Then as a school trustee, I was an employer (representing a school board) that negotiated with teacher unions.

The money teachers pay toward their union is called union dues or membership dues and this money is used to pay for many things.

These dues pay salaries of the union officials who organize teacher meetings or who arrange the professional learning teachers do when students stay home on a professional development (P.D.) or professional association (P.A.) days.

They support teachers in many other ways too, like representing teachers in negotiations with their employers, the school boards, if either teachers or the school boards want to change the terms of employment.

A portion of the dues a teacher pays to her or his union also goes into a bank account in case of a strike.

Agreeing on work conditions

The process for making decisions about wages (the money teachers make), working conditions and benefits is called collective bargaining.

Collective bargaining is a negotiation between the union representing teachers and a representative of the school board. In some cases, such as in Ontario, there could be provincewide bargaining legislation, which means that the position of the province’s ministry of education is the position that school boards are required to take into discussions.

When the union and employer come to an agreement, they enter those decisions in a document called a collective agreement. When an agreement cannot be reached, both the employer and the union have tools they can use.

The employer can prevent teachers from working and earning their wages by locking them out of the school. The union can strike.

No regular work, no pay

When teachers strike, they are refusing to perform their regular assigned work, and they don’t receive their pay from their employer.

Instead their union often pays them a small amount of money (about $50 to $100 each day) so that they can pay some of their normal expenses, like rent, food and transportation.

This money comes from the union’s strike account. The payment from the strike account comes from the membership dues the teachers pay each month.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit — adults, let us know what you’re wondering, too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]![]()

Charles Ungerleider, Professor Emeritus of Educational Studies, University of British Columbia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Popular News

Satisfaction with Canada's democracy declines significantly in Alberta

Tuesday, 28 January 2020 04:51 Written by theconversation

Andrew Parkin, University of Toronto

A functioning democracy depends on the support of its citizens. The popularity of specific leaders and political parties may rise and fall, but ideally without affecting the extent to which citizens are satisfied with the political system and have trust in its core institutions, including the executive, the legislature and the judiciary.

In recent years, concerns have been raised about the decline in confidence in democracy in many Western countries.

Read more: Are we witnessing the death of liberal democracy?

In the Canadian context, these concerns appear overstated: on the whole, satisfaction with democracy and trust in the political system in Canada has gradually been rising over the past decade, not falling.

This national trend, however, may disguise divergent trends at the sub-national level. Given the country’s decentralized federal political structure, it’s essential to look deeper by focusing on provinces and regions.

Using data on Canadians from the AmericasBarometer surveys, the Environics Institute for Survey Research examined a variety of questions related to confidence in the political system.

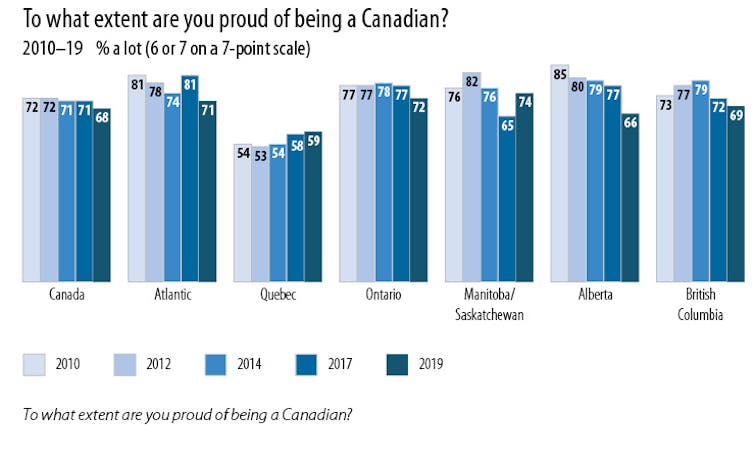

Polls of approximately 1,500 adult Canadians were conducted online five times over the past decade: in 2010, 2012, 2014, 2017 and 2019. These questions asked about satisfaction with, pride in, support for, respect for, trust in and approval of different political institutions or politicians.

In general, the survey results confirm that on these questions, national trends in Canada can be misleading, precisely because they often mask opposing regional ones. The answer to the question of whether Canadians are gaining or losing confidence in their democratic institutions depends in part on which region one is referring to. This can be illustrated in more detail by contrasting the trends in Québec and Alberta.

Québecers satisfied

Those concerned with national unity will find it reassuring that confidence in Canada’s political system in Québec is not significantly lower than average. This is notable given Québec’s status as a minority nation within the larger Canadian federal state — and one whose political leaders frequently contest the extent of the autonomy afforded to the province under the current federal arrangement.

Québecers are now slightly more likely than other Canadians to be satisfied with the way the political system works in Canada, and just as likely as other Canadians to be satisfied with the way democracy works. Québecers are also more likely than other Canadians to have a lot of respect for the country’s key political institutions, and just as likely to feel proud of living under the political system of Canada and to feel that that political system is worthy of support.

They have just as much trust as other Canadians do in elections, in Parliament and in the prime minister. They also have just as much trust in the Supreme Court, which is important since it is, among other things, the final arbiter of the federal-provincial division of powers.

Where Québecers stand out is on questions of identity. They are much less likely than other Canadians to feel a lot of pride in being Canadian (although very few feel no pride at all, indicating that while Québecers do not embrace a Canadian identity as strongly as other Canadians, most do not reject that identity either).

They are also much less likely to strongly agree that Canadians have many things that unite them as a country.

Trouble in Alberta

More worryingly, from a national unity perspective, is the finding that satisfaction with democracy and trust in the political system has declined significantly in Alberta.

Notably, the largest declines did not occur immediately after the start of the recession in the province in late 2014. The data suggest that Albertans initially remained hopeful, but that levels of satisfaction with Canadian democracy faltered after changes of government at both the provincial and federal levels in 2015 proved unable to quickly reverse the province’s economic fortunes.

To illustrate, in Alberta, between the 2017 and 2019 surveys:

• Satisfaction with the way democracy works in Canada fell by 19 points;

• Trust in elections fell by 10 points;

• Strong agreement with the proposition that “those who govern this country are interested in what people like you think” fell by 19 points;

• Strong respect for the political institutions of Canada fell by six points;

• Strong agreement that one should support the political system of Canada fell by 10 points;

• Strong pride in living under Canada’s political system fell by 10 points;

• Trust in parliament fell by eight points

• Trust in political parties fell by five points;

• Trust in the prime minister fell by 18 points; and

• Trust in the Supreme Court fell by 13 points.

In short, in Alberta, a decline was registered on a wide range of measures, and in each case, the decline was greater than that in any other region (in fact, in most cases, confidence in democracy in other regions improved over this period, with the exception of Atlantic Canada, which registered several modest declines).

Importantly, the declines are not limited to questions related to party politics (such as approval of the performance of the prime minister), but also to those related to support for the political system.

Slightly below average

These findings, drawn from a more comprehensive report entitled “Public Support for Canada’s Political System: Regional Trends,” show that these declines leave levels of confidence in Alberta only slightly lower than average.

This is because confidence in democracy was previously higher in Alberta than in the other regions. But even though Albertans don’t yet have significantly lower confidence in the country’s political system than other Canadians, they do stand out as the one region where confidence across a range of measures has declined sharply in recent years.

The main takeaway from this analysis is this: if the trend continues, a significant gap in support for the political system will emerge between Alberta and the rest of Canada.

Andrew Parkin, Executive Director, Environics Instittute / Sessional Lecturer, Munk School of Global Affairs & Public Policy, University of Toronto

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Impeachment trial senators swear an oath aimed at guarding 'against malice, falsehood, and evasion'

Monday, 27 January 2020 10:42 Written by theconversation

Susan P. Fino, Wayne State University

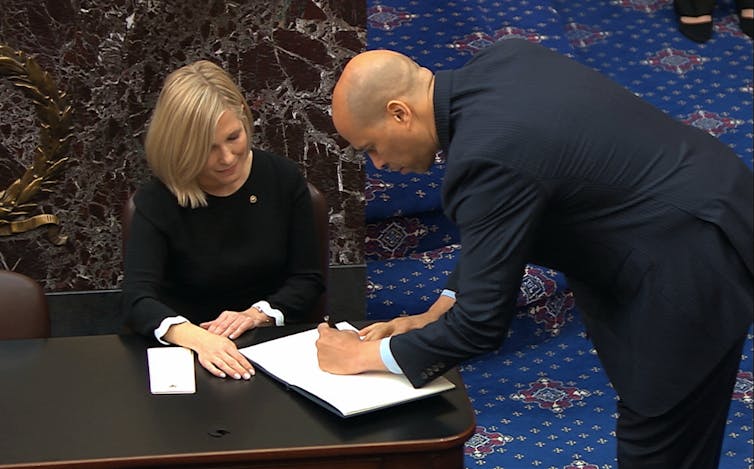

The 100 United States senators who are jurors in the impeachment trial of President Donald Trump have taken a special oath in order to take part in that proceeding. As they enter the active phase of the trial on Tuesday, this oath is supposed to govern their behavior.

It’s not the first oath that the lawmakers have taken in their Senate careers.

Members of Congress, as well as federal judicial officers and members of state legislatures, must swear to “support the Constitution.” But the Constitution does not specify the form of the oath. So the very first Congress crafted an oath of office and – with minor modifications – that is the oath each member of Congress swears when he or she takes her seat in the House or the Senate.

There is a second oath that members of the Senate must take when conducting an impeachment trial. The specific text for this oath was developed in 1868 for the impeachment trial of President Andrew Johnson. The rules for impeachment were revised by the Senate in 1986 for the trial of President Clinton.

The words of the oath and the requirement of a signature remain substantially the same: “I solemnly swear (or affirm, as the case may be) that in all things appertaining to the trial of the impeachment of (the president’s name), President of the United States, now pending, I will do impartial justice according to the Constitution and laws: so help me God.”

Senate rules also require that each senator taking the oath memorialize that action by signing an official register.

‘Require some guaranty’

Justice Joseph Story, in his Commentaries on the Constitution, written between 1848 and 1853, articulated the reason for the requirement of an oath in government:

“It results from the plain right of society to require some guaranty from every officer, that he will be conscientious in the discharge of his duty. Oaths have a solemn obligation upon the minds of all reflecting men, and especially upon those, who feel a deep sense of accountability to a Supreme being.” “[O]aths are required of those, who try, as well as of those who give testimony, to guard against malice, falsehood, and evasion, surely like guards ought to be interposed in the administration of high public trusts, and especially in such, as may concern the welfare and safety of the whole community.”

Certainly, a decision made by the Senate on removing a president from office counts as a “solemn obligation” that affects the welfare of the United States.

The requirement that each senator attest to the oath to do impartial justice by signing an official record is meant to emphasize the gravity of that obligation.

[ Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter. ]![]()

Susan P. Fino, Professor of Political Science, Wayne State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.